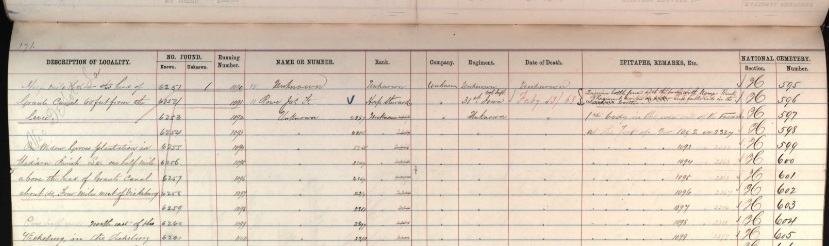

The list of burials in the Vicksburg National Cemetery in Vicksburg, Mississippi, testifies to the number of soldiers whose final resting place is in that cemetery. The number of entries marked as “unknown” silently memorialize the large number of remains that were unidentifiable. Not all burials in the Vicksburg National Cemetery have identities that will forever remain a mystery.

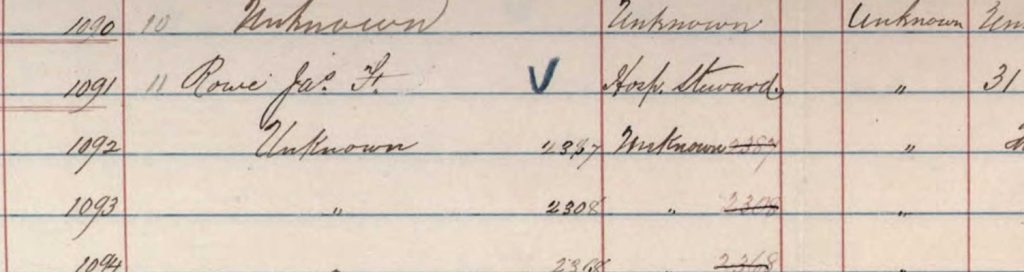

Such is the case with James F. Rowe, a young soldier from Davenport, Iowa, who died at the age of approximately nineteen in July of 1863 in Louisiana. Unfortunately Rowe was one of the thousands of young men who did not return home at the end of the war. The register serves as a reminder of the large number of unidentified soldiers who are laid to rest in Vicksburg.

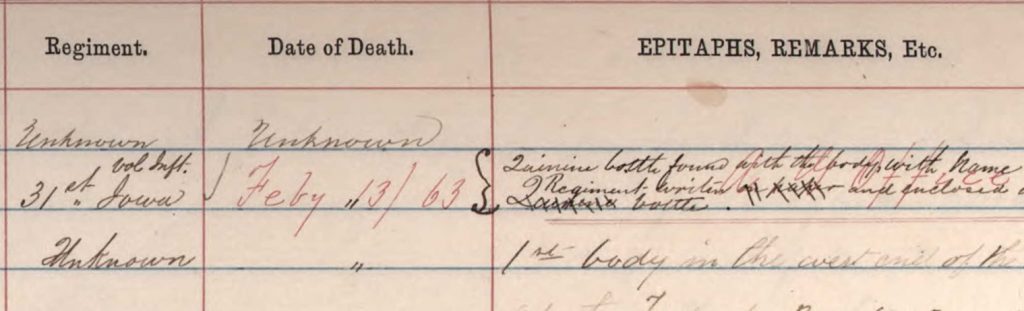

Rowe’s complete entry in the burial register indicated that he was buried in section H, number 596. Many of the entries contain scant information and little more than the word “unknown” filling in the boxes–not Rowe’s.

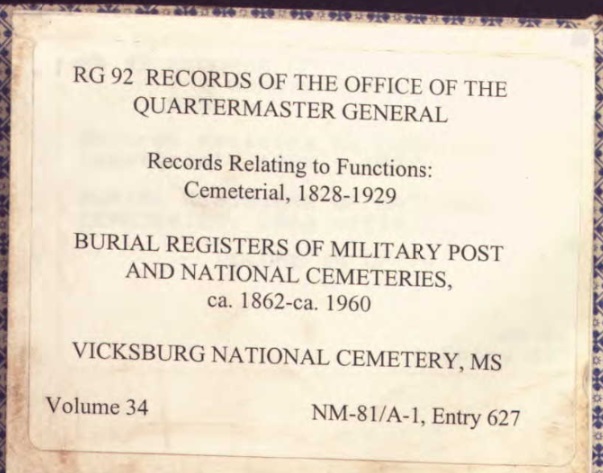

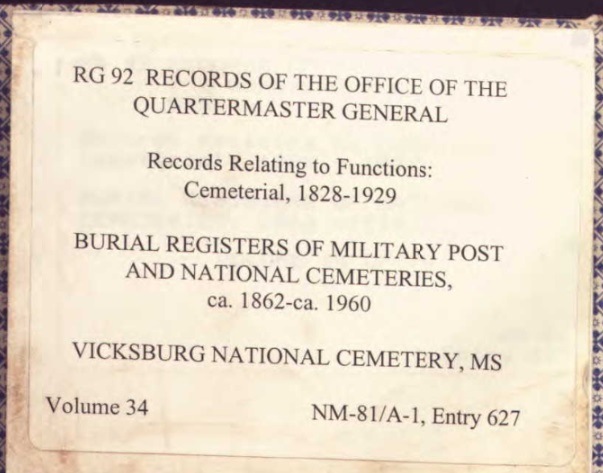

U.S., Burial Registers of Military Posts and National Cemeteries, ca. 1862-ca. 1960, Vicksburg National Cemetery, Mississippi, Volume 34; Original Field Sheet No. 170, Vicksburg National Cemetery, Section H, From No. 555 to No. 594, [page number 171 upper left corner], entry for Jas. F. Rowe; digital image Ancestry.com .

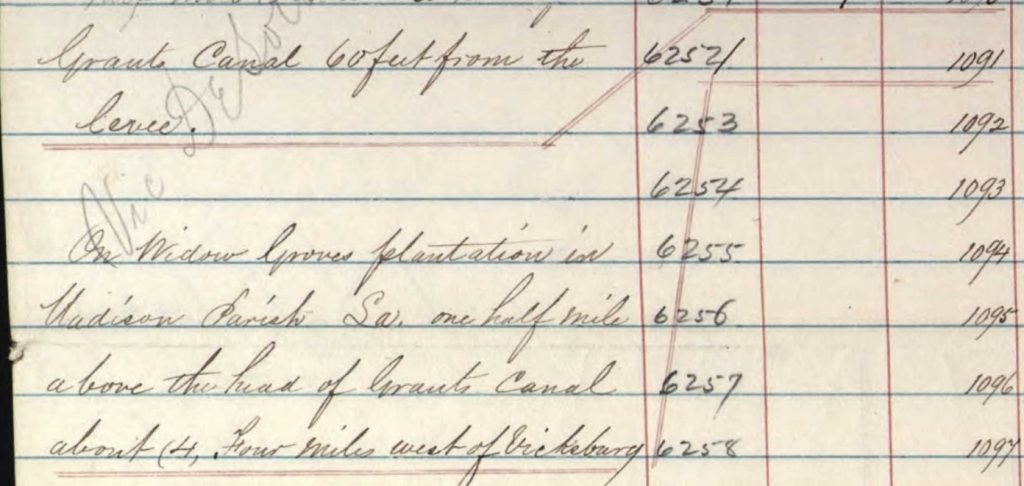

Rowe’s body was found “On Widow Groves plantation in Madison Parish La. one half mile above the head of Grants Canal about (4) Four miles west of Vicksburg.” Red lines separate his entry from the others.

The hospital steward’s date of death is given as 13 February 1863. It is written in a different hand and ink from the main information contained in the register and may have been written by the individual who made the lines around Rowe’s entry indicating where his body was found.

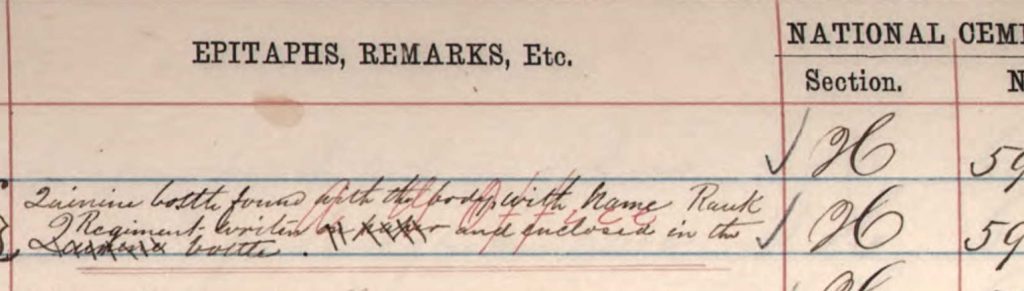

Identification of Rowe’s remains was made based upon a quinine bottle found on his body which gave his name, rank, and his regiment–the 31st Iowa.

The words “on paper” are crossed out, but something enclosed in the bottle had his information on it. The section of Rowe’s entry under the “Epitaphs, Remarks, Etc.” also contains a red notation that ends with the word “Office.”

The identification of bodies during the Civil War was a significant problem. Those with an interest in military dog tags, which came about as a result of body identification may wish to read Katie Lange’s “Dog Tag History: How the Tradition & Nickname Started” on the US Department of Defense website.

Rowe’s entry in the burial register for the Vicksburg National Cemetery was located on Ancestry.com in their database entitled “U.S., Burial Registers, Military Posts and National Cemeteries, 1862-1960.“

No responses yet