Reprinted from an article I wrote from the Ancestry Daily News — 23 November 1998

Just as there’s more to genealogy that family group charts, there’s more to discussing genealogy with young children than having them look at pedigree charts or fill out worksheets. What follows are some suggestions for bringing about an interest in family history in young children. If it doesn’t create an interest, it at least provides some suggestions for family activities. Readers should feel free to incorporate these ideas into their own activities or to create their own. Don’t feel bound by the suggestions offered here–there are plenty of other ideas as well.

Tell Stories

Are there stories from your own past that could be told to your children? Not stories dripping morals and tales of walking to school through three feet of snow, but stories that a child can understand, appreciate, and that are appropriate for their age. Stories about ancestors when they were the same age as the child are more likely to make a connection.

Bits and pieces of my own great-grandmother’s life formed the basis for a story I told my own children. The story was first told one night when the children wanted “one more story” and Dad’s eyes were too bleary to look at another printed word.

The story started something like this:

One upon a time, a long time ago, in a place called Nebraska, there lived a little girl named Tjode. She lived in a dirt house with her mother, father, and three little brothers.

When I first began telling the story my oldest child was six years old, the same age as Tjode was when the story begins. The story continues with details of animals walking on the roof of the house and Indians coming to the door. Later, additional age-appropriate details were obtained about sod-houses from several books on the subject and added color to the story and to the children’s interest (especially the part about the outhouse). Dirt walls and a dirt floor were quite a concept.

The story continues with the Tjode’s return to Illinois and her seeing her grandparents for the first time when she was eight years old. There weren’t many details about Tjode’s life until she began “working out” for a family in a local town (it had to be explained that “working out” meant cleaning and taking care of a house and not exercising). It was in that town where she met her future husband at the local church. On a cold Christmas Eve, Tjode marries Mimke (this was frequently referred to by the children as the “marrying part” and usually resulted in one child pretending to wear a bridal veil). Within several years, the family had seven children, one of whom is the great-grandmother of my children.

Tjode grew older and before long had several grandchildren of her own. The story continues with one of her granddaughters coming to visit. Tjode would give the child one piece of pink candy from her bureau drawer. “Do you know who that little girl was?” I would ask the kids. They would squeal with delight when they remembered the little girl is now grown and is their own grandmother. Tjode gets older and eventually dies. Her husband Mimke gets really old and the granddaughter has now grown up. One day she visits her grandpa Mimka with a little package wrapped in a blanket. “Do you know what was in that blanket?” the girls are asked. It was your Dad! A few more squeals of delight, occasionally followed by questions (“were you really that small?” etc.). “Your grandma has a picture of Mimke holding that little baby. We’ll have to get her to show it to you someday.”

The story was especially poignant when the girls’ grandmother (Tjode’s daughter) stayed the night and heard the story herself. As she listened, she added more details about her childhood visits to her grandmother. A few of which I had never heard before (the genealogist is ALWAYS on the move for additional facts!). Telling the story provided the children with a connection to their past.

If your own children are too old, are there grandchildren or other young relatives who might be interested in such stories? Write the story and send it to the child (making certain it’s wording and vocabulary are appropriate). Perhaps the child can even make illustrations for the story and send those to you, creating a new memento based upon an old story. It’s not important that the story be “literary” or written for publication. What is important is that it is shared with future generations.

Are your stories lacking details? While it’s important not to make up details up entirely, a certain amount of liberty may have to be taken. There are many historical books and sources that may provide additional details about the immigrant’s journey, pioneer life, etc. Maybe your grandfather did not speak English until he went to school, maybe your grandmother always made a special kind of cookies at Christmas, etc. There are many possiblities.

When using such stories make certain they are age-appropriate and do not frighten the child. It’s okay for the story to have a moral, but don’t overdo it. I have another ancestor who accidentally shot himself when his oldest daughter was five and the youngest was three. Telling my children this story at too young an age will cause them to worry the same thing will happen to their father. Scaring or causing needless anxiety in the children defeats the purpose of telling the story.

Omitting certain details from the stories you tell children may be necessary. It’s probably not crucial to mention to a small child the fact that great-great-great-grandmother’s first husband accidentally killed himself, her second husband left her after three months, and that her third and fourth husbands were the same man (and she divorced them both!). Omitting details from a story you would tell a child is entirely different from your Great Aunt Myrtle who refuses to tell you as an adult anything about your relatives.

Are there no “good” stories in your family? Perhaps you have no stories of your ancestors, or the memories that you do have are unpleasant and not things you want to tell your younger relatives. See if there are some pleasant memories, if not learn about pioneer life and extract appropriate details around your ancestor’s lives. If this is not possible, learn about early holiday customs for your area or ethnic group and incorporate these into stories.

Use Pictures

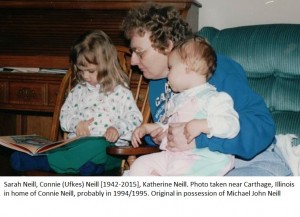

Children respond well to pictures, especially when a connection can be made to them. My great-grandfather had a sister who had the same first and last name as my daughter. A picture of the entire family taken ca. 1890 includes this lady as an eight-year-old child. We have another picture of this same lady at the age of approximately eighty sitting in a chair with me at the age of three standing next to her. This picture helped to connect my Sarah with the Sarah in the 1890 picture.

Are there events taking place that have some connection to your family or ethnic background? One year around St. Patrick’s Day, the children were showed the pictures of their Irish ancestors. When Dad wouldn’t let the kids take the original pictures to school, my daughter asked if she could draw their picture. And so her kindergarten teacher got to see a child’s renderings of her two Irish ancestors (complete with their names written underneath).

Take Vacations

Genealogists love to take research vacations. While genealogical vacations are difficult with a spouse, they are even more problematic with small children. Aside from children’s pizza parlors, there aren’t often places for children to visit when parents travel to do research (it seems like all my ancestors lived in remote places that are now fifty miles from a McDonald’s or a motel). When we visited Nebraska a major stop on our trip was a “dirt house” because great-great-grandma Tjode had lived in one as a child. Since a connection between the house and the kids was already established (by the bedtime story), they were more interested in it than if I had simply told them about it on the morning of the trip.

See if there are any historical spots near where you will be doing research. Children can also look at tombstones, noticing the different types of stones and engravings. Care should be taken with small children at cemeteries, however. Old stones, on unstable mountings, have been known to topple and in at least one instance a child was killed by a tombstone as it fell to the ground.

Signatures

Children love to write their name. Do you have any of your ancestor’s signatures? Make copies for the kids to look at. You can even discuss how the ancestor made his or her letters. This can be especially interesting if the child has a relative who has the same first name as the child.

But I Don’t Have Anything

What if you don’t have stories, photos, or other mementos upon which to base a story or activity? While making them up is not really an option (after all, you don’t like it when relatives make up answers to your genealogy questions), there might be possibilities. It may be possible to learn details about the time in which your ancestors lived by reading and studying the era. There are books on history and everyday life that may provide relevant details. I wish I had stories about my other great-grandmothers beside Tjode, but I don’t. I can’t tell the kids a similar story about great-grandma Fannie, or Ida, or Trientje. I wish I could. Telling such stories or creating other activities can bring a sense of connection and be a way to pass the information on to future generations. Maybe that’s why you should encourage your relatives to tell you such stories and why you should write down such stories yourself. So that your kids, if they are so inclined, will be able to tell them to their own children. After all, don’t we all wish our great-grandparents had done that?

3 Responses

Thanks for the great suggestions for getting the younger members of my family interested in my passion.

Excellent ideas. My grandkids are now 13, and beyond the bedtime story stage; but they do still enjoy hearing brief anecdotes – especially about the idiosyncratic personality quirks of various ancestors. For instance, my great aunt Winnie was a lifelong Catholic, but also superstitious. If a holiday dinner ended up with the table set for thirteen, Aunt Winnie would take her plate of food to the living room and eat alone, off of a TV tray. In her later years, every morning she would complain that she “hadn’t slept a wink.” After falling asleep watching soap operas, she insisted that she hadn’t napped, but was merely “resting my eyes.”

Beautifully written! As an early childhood teacher (and story teller) I heard signs of remarkable

choices that were so age appropriate and history appropriate — and that will follow your children and their children through the years. Hopefully many of your readers will find a way to

include similar events in their own stories to the young ones in their families.