[We’re reprinting this after some minor editing]

It is June 3, 1860.

Anna Gufferman, who is twelve years old, sees a stranger approaching her small home. He looks reasonably dressed and does not appear to be carrying a weapon. Illinois is not as wild a place as Nebraska where her cousins live, but mother has warned her that one can never be too careful. She shoos her five younger siblings in the house as the man approaches.

He approaches the front yard and calls out for the man or the woman of the house and says he is here to ask questions for something called the “census.” Anna is wary of calling for her parents if there is no need. When Father and the boys are in the field, he does not like to be disturbed, not even if Grandfather comes. Mother is down at the creek by herself, having left Anna with the children. The weekly washing is one of the few times Mother does not have several small children underfoot, and Anna is hesitant to bother her if it is not absolutely necessary. Anna decides this “census” does not require her to disturb her parents. She tells the census taker that she is very familiar with the family and the goings on in the household. After all, she is twelve years old and responsible for several younger siblings.

The census taker asks Anna several questions, which she frankly thinks are none of his business. He tells her that the government needs to know this information and that it is important it be accurate. Anna does the best she can to answer his questions. He starts by asking her the names of her parents and her siblings.

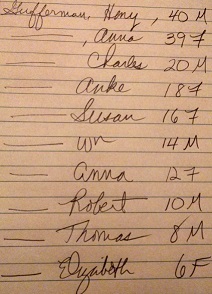

“It is a good thing my parents are not here,” Anna thinks to herself. While her English is rudimentary, it is considerably better than the handful of words her parents have managed to learn. Determined to impress the census man with her knowledge of English, she indicates that her parents are not Hinrich and Anneke Gufferman, but that they are rather Henry and Ann. Her other siblings all have names more German sounding than Anna’s. She decides to provide the census taker with English versions of their names, just as she did with those of her parents.

Anna is not quite certain how old her parents and her siblings are, but the man seems to insist on knowing their age precisely. Their christening names and dates of birth would be in the family bible, but Mother would fly into an absolute rage if Anna got the bible herself and began leafing through it. Deciding it was not worth the risk of her mother catching her in the act, Anna guesses as to the age of her parents. Despite her uncertainty, she speaks clearly and distinctly to convince the census man that she knows the ages precisely. He seems pleased to get the information.

He then asks where her parents were born. Anna knows they were born in Germany and were married there. Those questions are easy. The census man then asks where she and her siblings were born. These questions are not so easy. She cannot remember which of her older brothers were born in Germany and which ones were born in Illinois. She remembers that her parents lived for a while in Ohio before coming to Illinois. And frankly, she is getting tired of all the questions. Consequently she tells the census taker that her two older brothers were born in Germany, the next was born in Ohio and that all the remaining children were born in Illinois.

Anna decides to give hurried answers to the rest of the census man’s questions. He has taken time away from her chores and Mother will not be happy if the morning tasks are not done when she returns. Occasionally impatient with Anna’s delayed answers, the census man seems pleased when Anna begins answering the questions more quickly. Eager to please and knowing she should return to her chores, Anna speedily answers the remaining questions, paying little concern to the accuracy of her answers.

It is June 25, 1880.

The census taker arrives at the home of Hinrich and Anneke Gufferman.It is a different place than his fellow enumerator encountered in 1860. Hinrich and Anneke have two children at home, the youngest son who helps his father farm and a daughter who works as a hired girl for a Swedish couple up the road. There is still plenty of work for Anneke to perform around the house, but no longer meeting the needs of twelve children makes her life less harried than it was before.

Anneke invites the census taker into her kitchen and after he indicates some of the information he needs, she goes and gets the family bible, which contains the names and dates of birth for her husband and her children. She opens the bible to the appropriate page and tells the census taker there is the information. The entries are written in Hinrich’s bold, clean script and the census taker only has difficulty in reading the name of the youngest daughter Trientje, which he copies down as Fruita. Otherwise the odd-sounding names are easy to read and the census taker simply copies them into his record.

There are additional questions and Anneke provides the answers as best she can. In Germany, her husband was a day laborer and had moved several times looking for work. When asked where her husband’s parents were born she is not certain; Hinrich’s mother died when he was a baby and the father had died shortly after their marriage. Anneke told him the parents were born in Germany. Anneke was not certain of her father’s place of birth, either. He had died before her birth and had been a soldier. Anneke had been named for her father’s mother, with a first name that was unusual for the area of Germany where she was from. Thinking her father was Dutch, she told the census taker that her father was born in Holland. But she was not really certain.

It is June 16, 1900.

The census taker comes to the door of Hinrich Gufferman. It has been a month since his beloved Anneke has died. Hinrich does not know the census taker. He swears at him in German in a booming voice and the enumerator senses that he will get no answers. Gufferman’s son Johann lives a few miles up the road, fortunately in the same township. The son had told the census taker that Hinrich was taking the death very badly and was only speaking to a few family members. Johann told the census taker to come back if information was needed on the father. It looked like the enumerator would have to take Johann up on his offer.

Ever wondered why some census entries look like creative accounting? Have you ever thought about what actually transpired when the census taker arrived at your ancestor’s home?

(c) 2014 Michael John Neill–this article originally appeared in the Ancestry Daily News and is used by the author on his blog with permission. Any other reproduction or publication is not permitted.

6 Responses

In the 1940 census my mother’s occupation is listed as “maid.” She still lived at home, and she pumped gas at her father’s filling station, she worked at the family barbecue, and she also worked at a local fuse factory. But I can hear her saying to the census taker, “oh, I’m just the maid around here” and the census taker solemnly writing it down, not understanding Mom’s sense of humor.

Yes, looking really close at the census’ from every time they were sent out to seeing if there r mistakes and what they r help us too.

I could not find my father’s family in the 1920 census in Dunkirk, NY. At a later time I was looking for a different family and found mine. Our family name of Schmitz was written as Schrantz which was the name of several families in the area.

Does anyone know what the size of the original census forms were from 1900 forward?

[…] example ever of how the census data ends up the way it is: The Census Taker Cometh by Michael John Neill on […]

I was teaching a “census” class one day and had them look up my grandparents in 1910, knowing they were there and would be “appropriate” for newbies. Never be too sure of yourself! As I found the entry, it clearly said…”Royal Edgar and Bessie Lincoln…with four children: Bob, Walt, Maude, and Vivian.” Wait! I know that family well…knew all of them from the time I could talk and listen…and no one was named Vivian! As I looked at the dates, I saw that Vivian was born at the same time as my mother. But my mother was Lydea. I came to full stop and looked at it carefully…The writing was clear. The dates all looked right to me. But who in the world was Vivian?!! Then the story that mom had frequently told came to mind. She said that her parents had “fought” for six months over what to call her…they each had their own favorite and neither was willing to give way.

What happened? I made this explanation up but I am quite sure I am right. The census taker came by when Grandpa was at work. When he asked the baby’s name, Gma said, “Vivian.” I also think that when Grandpa got home and heard the story, he put his foot down and named the baby his choice: Lydea Rebecca. (Lydia was his grandmother, Rebecca was his mother.)

I don’t think my mother ever knew of being called Vivian…because she never told me that story. And I don’t know where Grandma got the idea. But mom was never again called Vivian. (Although she did change her name from Lydia to Lydea when she went to high school…)