Ulfert’s wife died intestate less than 24 hours after he did and still was given a “widow’s award” in his probate and consequently had her own probate file to settle up the widow’s award.

Today’s Genealogy Tip of the Day, “Build Your Skills By Learning More on a Done Family” was necessarily short so I’ve decided to expand more on it here. Generalizing is fraught with the potential for exceptions and errors, but we’ll go ahead and trudge on anyway.

One of the challenges with pre-1850 American research (especially outside of New England and that’s where this discussion is concentrated) is that there are generally fewer records during this time period than there are afterwards. Other than wills and the occasional deed, the extant records during this time period tend to make fewer direct statements regarding biological relationships than do later records. That’s one reason why research during this time is more difficult. Fewer records in general only aggravates the problem.

That’s why it is imperative that the researcher understand the research process; be methodical; be aware of social patterns, the importance of the social and kin network, migration trends and motivations, and the underlying legal structure and framework upon which most records are created.

It takes a while to develop those skills and that perspective. Even if one comes to their genealogical research from a research-based background, genealogical research in the pre-1850 time period requires several concomitant skills.

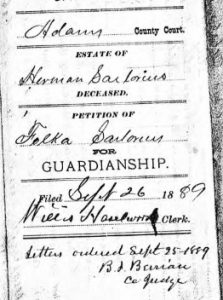

Volke (Behrends) Sartorius became guardian for her children simply so she could sue her deceased parents’ estate for their wages.

Developing those skills can be done in many ways, but actual research is the best way. The problem is that it can be difficult to develop those skills while working on a family during this time period, especially a family that has never been worked on before. It can be done, but it’s difficult.

One way to improve one’s research skills is to completely research an entire family that is a little better understood during a somewhat later period when the records are more detailed and to get every record on that family that is extant. Every record. Reading all those records when more is already known about the family helps the researcher to understand various nuances in the records, particularly terms of “unwritten” social constructs and legal practices.

Quitclaim deeds will serve as an easy example. When one already knows when the widow died (because there was a record) and one sees a quitclaim deeds for the farm drawn up a month later, it’s easier to understand the flow of these records and the underlying process involved. Skills are best learned with easier problems first. In a land-platting seminar I give, the first problem is to “fit together” a series of partition deeds that were drawn up and platted at the same time–they are supposed to fit together perfectly and it’s a good way to start learning the process instead of picking a series of supposedly adjacent colonial patents with incomplete descriptions surveyed over seventy years that may not fit together easily.

That way, in an earlier time when there are fewer records and a complete chronology cannot always be developed, one already has an understanding of the entire process and can better understand the records that are left behind.

I’ve often thought that researching my Ostfriesen immigrant ancestors to Illinois and Nebraska during the 1850s-1880s was of great help in researching my Southern families during a much earlier time period. I located every record I could on them: land, probate, vital, church, cemetery, military, passenger list, pension, etc. Of course all those records are not extant nor applicable in Virginia in 1700 and the legal process is somewhat different. But going through all those records helped me to understand quite a bit and when there was a record I didn’t understand I often knew things about the family from other records that helped me to understand the record in question. And researching those families reinforced the importance of the extended kin network because it was easier to research “those other names” on documents in the late 1880s than it was in the early 1700s. It was easier to see that witnesses, bondsmen, etc. were related because I knew the names or could more easily research them.

And I knew my Ostfriesen ancestors were probably no less clannish in Illinois in 1870 than my Virginians were who moved to Kentucky in 1790.

If you’re “stuck” on a family pre-1850 and you’ve not done much research in that time period, consider extensively researching your post-1850 families–or at least one of them.

You may learn more than just a few new details of your family’s life. You may improve your research process as well.

Of course when moving back in time or crossing hundreds of miles, research is different in some ways. That’s always a good question to ask yourself too:

How is my research in this time period and location different from my research in other time periods and locations? And…how is it the same?

Not being able to answer those questions could be part of the problem.

3 Responses

This is excellent and helps pull together some thoughts I have been having about Eastern European research. I have always told new researchers that they need to exhaustively research their immigrant ancestors and collateral relatives before trying to jump the pond. In knowing as much about those immigrants as possible, one may better be able to recognize them in records in the old country (where their names might have been slightly different).

You have provided an additional important reason to enhance one’s skills before testing them in places where the records may be scant, difficult to find, in several other languages and created under different cultures and laws. The skills and insights one develops under better research circumstances will provide the foundation for addressing more difficult research questions and circumstances.

Michael, Emily makes a good point. There is an advantage to really learning all you can about a single ethnic group. My “crossing the pond” was easy for my mother’s mothers side– lots of records here in the U S. But work on these “easy” ancestors allowed me to know the right questions to ask of the right people. Building a network of similar minded genealogists gives us another kind of resource.

There’s a big advantage in doing that. Crossing the pond on all my mother’s Ostfriesen ancestors was easy (except for one), but fully researching them in the United States really helped to develop my understanding of all the records (local and otherwise) that one needs. And it didn’t hurt that all those name variants, incorrect spellings, and “which patronym are we using today” situations kept me on my toes.