We all have gaps in our experience and education. The gaps are not the real problem. The problem is when we don’t admit that we have them.

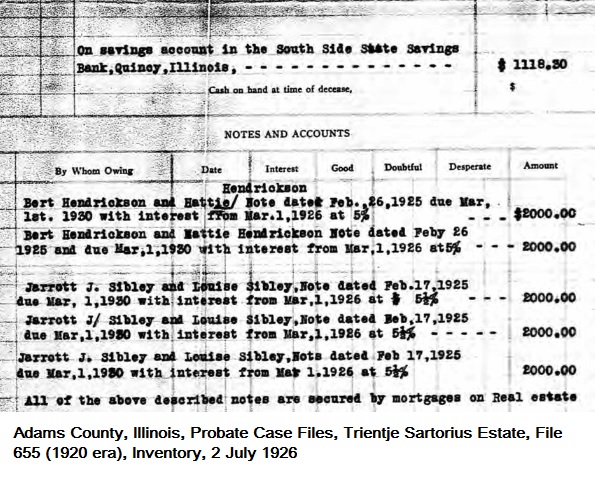

The estate settlement’s inventory Quincy, Illinois, resident Trientje Sartorius indicated approximately $1000 in a bank account and $10,000 in real estate mortgages executed by two separate individuals. The executor’s report indicated that the ability to collect on the mortgages was good and there was little chance of default. The estate accounting showed that interest was being received on the mortgages and they actually were sold for their full value during the settlement of the estate.

The individuals who owed the estate money were not family members or known relatives of the deceased.

I initially thought this was unusual. I had not seen similar inventories and I had seen a fair number of them. Then I got to thinking about how I really had used estate inventories and probate records in my research. In many of the 20th century probates I had used, I was concerned about learning the names and addresses of heirs to the estate. In most probates during that time period those details are fairly clear and explicit. One is not reading between the lines to determine relationships and residences as one would with records from an earlier era. In an earlier era, we are more likely to look at every little clue we can get. In most of my research in 20th century estates, I did not have to do that.

And for me, that was the problem.

Most of the estate inventories that I had “really used” for research and exhaustively looked at for clues were ones before 1900. I reviewed every page in the file looking for relationship and occupational clues. I had not done that for 20th century problems.

So I did not have any point of reference with which to compare this inventory. I could not say if holding notes of this type was common or not for someone with the amount of money the widow Trientje had in the 1920s.

That means I need to do more research: look at other probate files, determine if real estate investment of this type was relatively common, find out who the mortgagors are and where the property was located. After all, are these local people and is this local property?

Questions and more questions.

It is always good to step back and analyze your experience before making a conclusion about something. Ask yourself:

- how is this situation different from others I’ve researched?

- how is this situation similar to others I’ve researched?

- how many records have I used of this type during this time period?

- have other families I’ve researched during this time period all been from the same social and cultural circles as this person? Or is this person different?

All of those are separate questions from why Trientje may have chosen to invest in real estate loans instead of other options in the 1920s? And what were those other options?

The estate of Trientje was referenced to see if it provided an address for her youngest son. And now it has left me with a stack of questions–about her, 1920s-era investments, and my own experience.

One response

Warren Harding was President and after he signed the papers, he apologized to the Public that he had just sold the United Staes. He initiated the Federal Reserve.

This might have affected the investment market?