I understand why people want to trace their lineage as far back as they can as quickly as they can. Skipping back as quickly as one can may hinder the development of adequate research skills.

I understand why people want to trace their lineage as far back as they can as quickly as they can. Skipping back as quickly as one can may hinder the development of adequate research skills.

On the one hand most of my maternal ancestors were relatively easy to trace in the United States. They were all immigrants from Ostfriesland, Germany, to the Midwest between the 1850s and 1880s. With the exception of one, the village of birth overseas was known by living family members. Genealogies had been published on several of the families. For the most part, church, census, and vital records in the United States made establishing parent-child relationships a simple matter of finding those records and reading them. I didn’t “have” to use other records to clearly establish the family connections. Researching the families in Ostfriesland was usually a matter of using the appropriate church records once the village was determined.

Researching my paternal lines was another matter entirely. Researching families in rural New York State before 1830, Virginia before 1800, Kentucky before 1830, Pennsylvania before 1850, and other areas can be more difficult due to type of records that are extant. It can be done, but it is not always as easy.

What helped me in those areas was that I completely, exhaustively, almost obsessively researched my maternal and paternal families in Illinois post 1850, even when I didn’t “need” the records to establish the relationships. It is easier to find land, court, probate, and other records when one already knows the relationships and the dates and places of vital events. Using those records provided me with a deeper understanding of those ancestors for whom I thought I knew everything. But it also provided me with something else:

a deeper understanding of the records

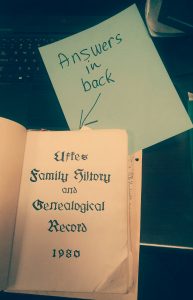

It was sort of working a math problem when the answer was in the back of the book so that I could check.

It’s a little easier to understand probate and court records when you already know all the family relationships, particularly those that are not stated. Land records that suggest relationships (but don’t state them) are easier to understand as well when the relationships and dates of events are known. It’s easier to see that a quit claim deed was frequently drawn up after the surviving parent died when you have all those death dates. My understanding of all those records was enhanced by my underlying knowledge of the families.

And that help me on those families where I didn’t already know the relationships.

Research in certain areas of the United States before vital records were kept can be difficult. The problem is compounded when certain records have been destroyed or lost. It makes the use of the remaining records even more important and the ability to understand and interpret those records crucial. Those records often don’t explain things as completely as we would like. For that reason it’s always advised to understand how records fit into the larger record keeping process and the legal process that generated many of those records.

A really good way to do that is to fully research a family or group of families that you already “know,” perhaps in a slightly later time period when there are more records. The legal structure will be the similar (although state statute can change), the organization of the records will be similar, and the way people behaved won’t be all that different. Fully researching that family will improve general research skills, improve one’s ability to understand and utilize materials that are found.

After all, if you’ve never really looked through and completely analyzed a series of post-1850 probate records, how well can you analyze ones from 1800? Of course there are differences, but there are similarities.If you’ve never completely analyzed all the deeds on an 1880 era ancestor, are you really prepared to completely analyze those for a 1790 ancestor?

And that might be what you’ll have to do for that Virginia relative who is giving you difficulties.

If you’re stuck on many of your relatives in areas or time periods where there not good vital records, consider fully and completely researching one or more of those families that you think you already have “done” in time period and location where there are better vital records. Find everything. Analyze everything. Interpret everything.

At the very least you’ll have a better understanding of those relatives that you think you already “know everything about.”

And there’s always the chance that you will have improved your research skills to help you with those that you don’t.

3 Responses

This is such a good suggestion. I need Virginia and Kentucky info so I will start with who I know.

Thank you! I’m about to pull my hair out over a 2x great-grandmother born about 3 years post-Civil War in Alabama. I think she was illegitimate from everything I can see, so I may never discover her father, but I want to be sure.

I wonder if your 2G-grandma may have run afoul of a passing Yankee? That would certainly make it more difficult to locate the father, and would account for a lack of information in family records. Is the time and place a possibility? Good luck with tracking down the guilty northener. (Those two red lines (in my copy, at least) indicate that I didn’t put in enough info…I assume that means I didn’t give his name. Would that I could so that you would know. ).