Ancestry.com‘s “Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1879-1903” has recently been updated on their site. They originally published it some time ago, so it is doubtful that it contains any significant changes.

The database does serve as a reminder that everything is not always as it seems–or at least not titled 100% accurately. Given that it is a nationwide alphabetical index, it can be a way to learn where a relative is buried if that location is unknown. For known burial locations where stones are illegible or missing, it can be a way to determine what was on that stone originally. Just keep in mind that a transcription one of these cards is not the same thing as a transcription of the actual tombstone. Never indicate you have seen something you have not. Your citation for this “tombstone” should be to this Ancestry.com database indicating that it was created from National Archives publication M1945.

Like many of Ancestry.com‘s databases, ” “Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1879-1903“” is created from material at the National Archives–which is why that’s included in the citation. In this case US National Archives microfilm publication M1945 was digitized to create this database. The US government began issuing headstones in 1879 for servicemen buried in non-military cemeteries. This database is created from microfilm copy of the cards that were created to keep track of the stones that were purchased by the government.

The vast majority of the stones were issued for men who served in the US Civil War. But there are a smattering of entries for men who served in military action before that time. The title is ever so slightly misleading.

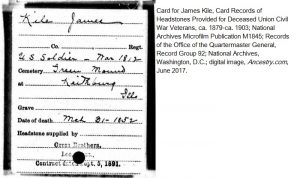

James Kile served in the War of 1812 and is buried in the Greenmound Cemetery in Keithsburg, Illinois. His stone is no longer extant. He apparently had a stone at one point in time based on the card that appears for him in this database. The card does not indicate any specific details of his service, but does indicate his date of death was 31 March 1852. While there is no reason to doubt the date of death at this point, the card would provide secondary information as to James’ date of death.

Later cards for tombstones issued for burials in private cemeteries indicate the units in which the veteran served along with some annotations suggesting that information was compared to actual military records before the stone was issued. There’s no such notation on James’ card. There’s no reason to doubt his service as most of these cards have no such annotations. That’s why it’s always good to look at more records than just the one of interest. There’s no way to know what is unusual and what is not when one only looks at one record in a dataset.

No responses yet