Typically one does not look for estate settlement information on someone who has not lived in an area for six years. Typically one does not expect an estate inventory to be filed ten years after someone has died in a county that he left nearly fifteen years ago.

And typically not looking everywhere is why some of the best finds are not located.

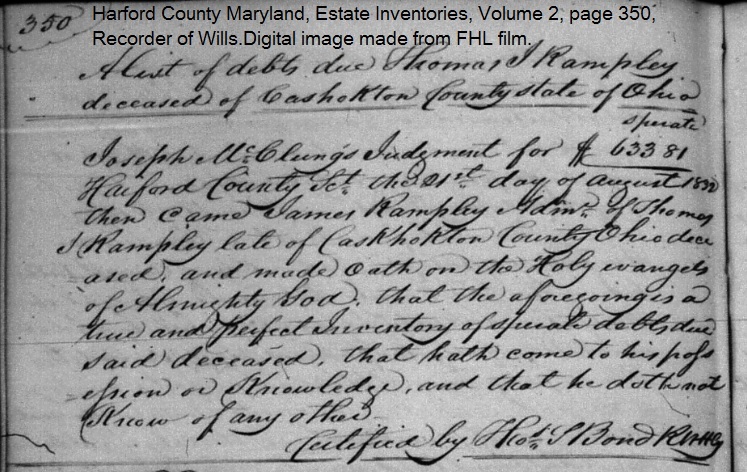

This 1832 inventory from Harford County, Maryland, indicated that Thomas J. Rampley was due money from a judgement received against a Joseph McClung. The judgement stemmed from a property dispute involving real estate Rampley sold to McClung before he left Maryland in 1817.

The document even styles Rampley as “Thomas J. Rampley, deceased of Coshokton County Ohio.” Rampley’s estate in Ohio was probated in the early 1820s, shortly after he died there in 1823.

Records like this are one reason why the “exhaustive search” needs to be look in every damned location you can think of even when the person might have been gone for a while, the person “shouldn’t be in the records,” you don’t think that record will help solve your problem, etc. I understand the theory behind an exhaustive search, but some of my best finds have been made when I just looked and looked and looked. That’s especially true in the pre-1850 era. Look at everything.

Genealogical conclusions can always be revised if new information comes to light and even steroid-induced comprehensive searches will miss things.

But when you think “you’ve got it all,” you are asking to be surprised.

One response

It can be even longer. About a month ago, I stumbled across a chancery suit on the Library of Virginia that was initiated in 1810 and settled in 1825. The suit was brought by the heirs of John Staton against the new husband of their mother, alleging that he had sold valuable property that belonged to the estate and left the state. It listed all the children and their spouses, gave the mother’s name, the name of the deceased father and the new husband’s name. It was a gold mine!