This image was used as an illustration for “Genealogy Tip of the Day”

I have so many Johns, Johanns, Janns, Jans, Janses (my attempt to “pluralize” Jans) in my genealogy, it’s a wonder I can see straight. Since it’s my middle name, I take the confusion in great stride. In different parts of my family the name “Johann” (and variants) had slightly different interpretations–depending upon the time period and the ethnic region in which it was used.

One should never generalize outside the immediate geographic and ethnic area in which one is working. What is true about one region and one time period is not necessarily true about another.

Erasmus and Anna Catharine (Gross) Trautvetter of Thuringia, Germany, had the following sons:

- Johann Heinrich Trautvetter, born 1791 Dorf Allendorf

- Johann Adam Trautvetter, born in 1794 Dorf Allendorf

- Johann Michael Trautvetter, born in 1796 Dorf Allendorf

- Johann Georg Trautvetter, born in 1798 in Dorf Allendorf

There were daughters as well, but our focus is on “Johann.” All the sons immigrated to the United States after their parents died in the Wohlmuthausen (Erasmus in 1841 and Anna Catharina in 1823). The sons all used their “middle” names as their actual names in the United States (except for one document George signed as Johann George). That’s because their first names were saint names given to them at their baptism. They did not actually use the “first name” of John.

Except again, for George that one time. But he’s the exception.

This naming practice was common in the time period in the location where the Trautvetters. It was common in other areas of Germany as well.

But not everywhere.

Just because something is done in one area of a country does not mean that it is done in another. Cultural practices are like that. They do not necessarily follow current political lines.

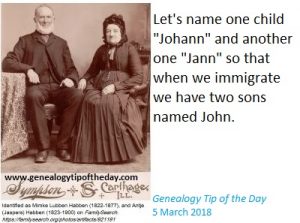

Mimke Lubben Habben and Antje Jaspers Fecht had several sons born in Wiesens, Ostfriesland, Germany in the mid-19th century, including:

- Johann Mimken Habben born there in 1853.

- Jann Mimken Habben born there in 1859.

Ostfriesland is different.

Johann and Jann are not baptismal names for these boys. They are the actual first names of these boys. Johann did not die before Jann’s birth. Jann was not named for him. Johann and Jann are different first names. Johann is a High-German name. Jann is a low-German (Platt) name. The names were different to their parents and the community into which they were born. They were family names of other members of the extended Habben and Jaspers families.

The family immigrated to the United States and, in an attempt to anglizice their names, both sons became John Mimken Habben (sometimes John Mimka Habben in an attempt to anglicize “Mimken” which is somewhat difficult). Yes, that is confusing. But that is because both names are equivalent to “John” in English.

Their “middle name” of Mimken is actually a patronym. All their siblings (girls included) had that middle name. Much like the first name being the actual first name, using the patronyms as second names during this time period (19th century) was a common Ostfriesen practice.

Whether your Johann Michael was really a Johann or a Michael and whether your Johann Mimken was actually a Johann, depends upon the time period. Whether your Johann became a John depends on the time period and whether or not he immigrated.

It depends.

Just like a lot of research–on the location, the time period, common practices, how much your ancestor (if he was an immigrant) desired to assimilate, etc.

And it depends on how much you become familiar with those practices.

Jim Beidler discusses the call name practice in his book on German research (The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide: How to Trace Your Germanic Ancestry in Europe ).

One response

Very enlightening information. I think this may help me sort out some of my German ancestors. Great boor reslurce also. Thanks!