Some of the things we “wish we were taught in history class,” we may have actually been “taught” or exposed to and have simply forgotten. If you don’t “use it, you lose it.” Many times these facts are readily available in a vetted reference book or other reliable source. It does not mean that we should not learn about them or be taught them–it’s just that they are often sitting there if we forget.

Then there’s the minutia of every day life that’s more difficult to discover.

The minor details of everyday life that rarely are taught. It’s the “big” events of history that matter to historians and most of the public (or the version of these events that people want us to believe). Genealogists need to know those events and have a good, broad understanding of history. But then there are times when we need seemingly trivial details.

Sometimes it is those mundane facts of life that confound the genealogist the most and are the things that we’d most like to know. Sometimes those details simply represent gaps in our knowledge, our upbringing, or our educational experience. Sometimes these details are commonsense to others and major epiphanies for the rest of us.

There’s some danger in publicly admitting that there are gaps in our knowledge. The real danger is not in knowing there are gaps but in refusing to admit that they exist. For me a burning question was why did relatives who had “money out on loan” to private individuals arrange those loans when they likely did not know the parties to whom they loaned the money? I’d seen several cases of estate inventories that indicated loans and mortgages held by my deceased ancestors to individuals with whom I was fairly certain they had no relationship

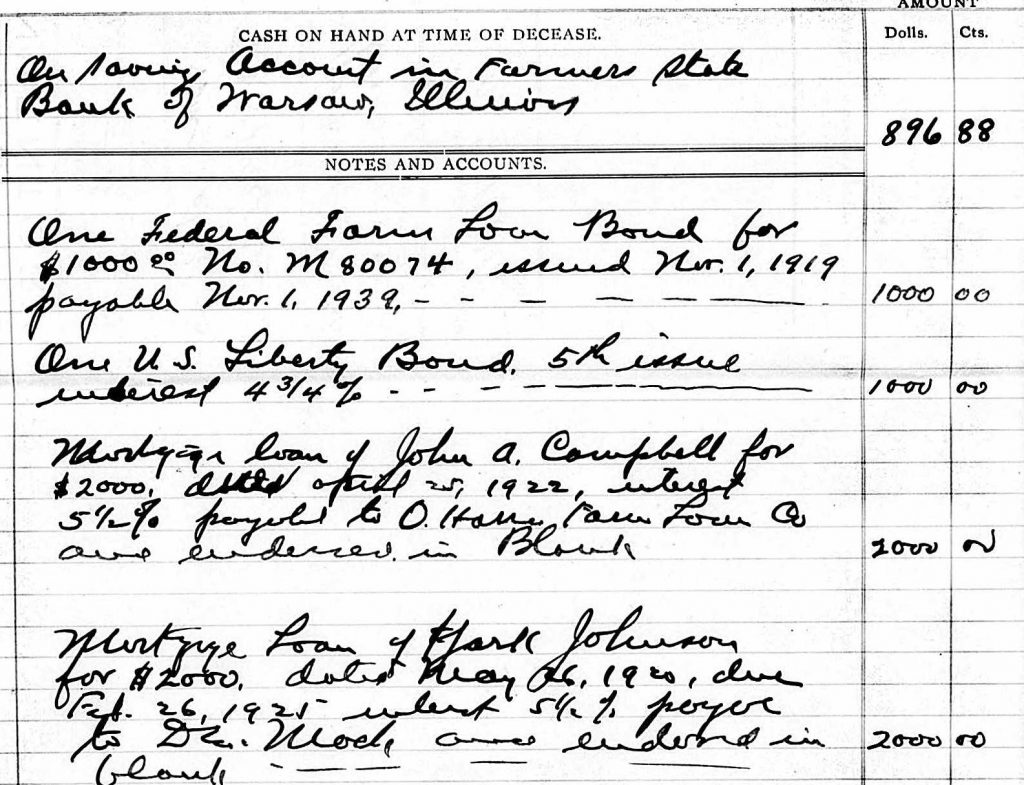

I knew the money was loaned out as an investment. That was not to difficult to surmise. That’s what my aunt who lived in Warsaw, Hancock County, Illinois, did. The inventory of her estate in 1920 indicated two loans for $2000 each in her estate inventory: one to John A. Campbell and another to Tjark Johnson.

Part of the inventory of the estate of Anna E. Trautvetter made out 23 September 1920, Hancock County, Illinois, probate case files.

The writing is a little difficult to read, but then Tjark is not the most common name and not the easiest one to spell either. Often written as Chark or Clark, the clerk writing the inventory likely spelled the name incorrectly and wrote over as a means of fixing it. There was only one adult male named Tjark Johnson in Hancock County, Illinois, and that was my uncle.

Anna E. Trautvetter lived in Warsaw and Tjark Johnson would have lived south of Carthage-both in Hancock County, Illinois. Trautvetter was my aunt by marriage (married to my second great-grandfather Trautvetter’s brother) and Tjark was my uncle by birth (a brother to my second great-grandfather Janssen). They likely did not exist in the same social circles, lived a distance apart, attended different churches, etc.

Typically one would research individuals to whom a relative lent money. That’s an excellent research technique when research is stuck on a certain ancestor. I did not do that in this case. Johnson’s family is well-documented. His origins in Ostfriesland, Germany, are known and his family has been traced and researched extensively. I’ve not been overly interested in Anna Trautvetter’s family of origin largely because her husband’s family is already traced across the pond, she’s an aunt by marriage, and one only has so much time to research.

How they came to be financially connected was an exceedingly minor detail in my research and, given that the families are well-documented in other ways, one rabbit hole that I decided not to go down (had I been “stuck” on the families, it would have mattered more.

Helms, J. C. Plat Book of Hancock County by Townships. Carthage, Ill.: J.C. Helms, 1908, page 28.

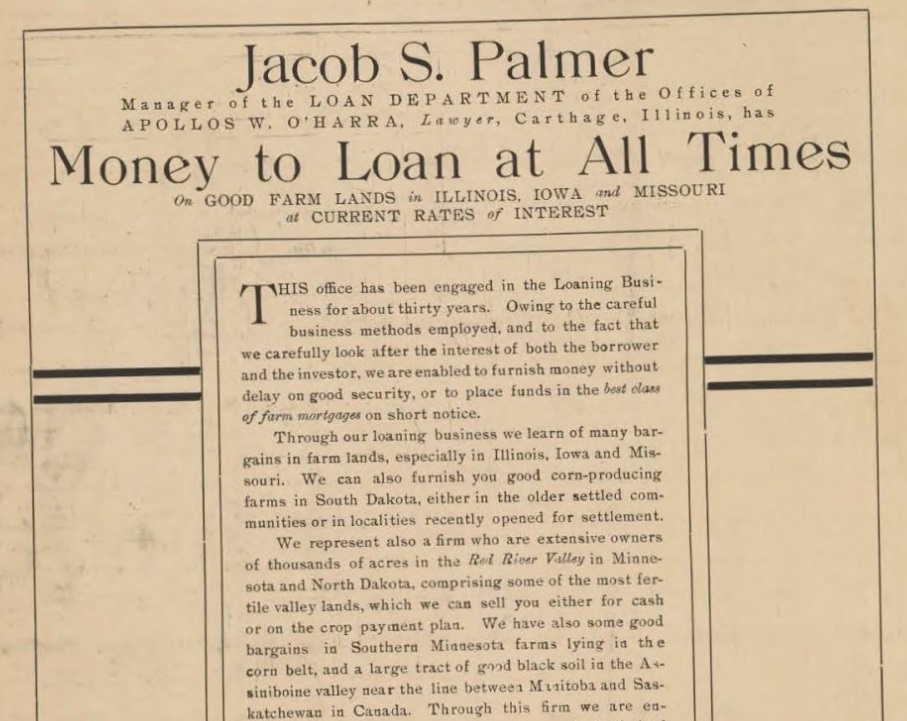

Then I was reviewing a 1908 plat book for Hancock County, Illinois. While scanning for the locations of interest, I noticed an advertisement in the book placed by Jacob S. Palmer, manager of the “land and loan” department of the law office of Apollos W. O’Harra in Carthage.

Helms, J. C. Plat Book of Hancock County by Townships. Carthage, Ill.: J.C. Helms, 1908, page 28.

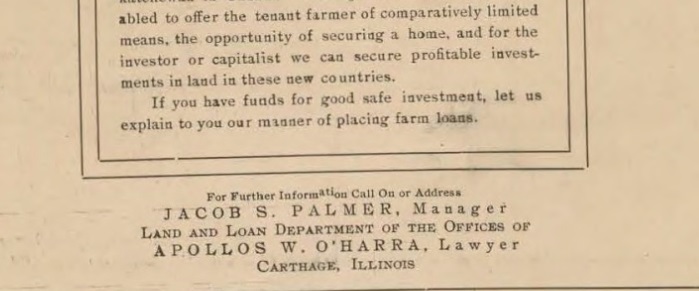

That ad explained the probable way that Trautvetter and Johnson came to interact financially. It mentioned the loan business manged by Palmer and ended with “If you have funds for good safe investment, let us explain to you our manner of placing farm loans.” Then it clicked.

Palmer worked as a loan broker of sorts for the O’Harra law office. Being a lawyer in the county seat, O’Harra would be aware of individuals who had financial difficulties as there would likely be court action taken against those individuals. Palmer (or an employee) would have easy access to public court records to help assess the credit worthiness of individuals.

I don’t know if Palmer facilitated the loans held by Trautvetter upon her death. There were other brokers who advertised in the plat book as well. But now I have a likely idea of how the loans were facilitated–and that explains loans held by several other relatives during the early 20th century as well when those loans were not made with relatives or close friends.

Sometimes it’s “good enough” to have an idea of how something likely happened without knowing the specific details. Sometimes.

Where Anna Trautvetter got the $4000 to invest and why it was separate from her husband’s estate is a separate question entirely. And one that’s a little more interesting.

No responses yet