There are a variety of things one can search for in newspapers besides the names of […]

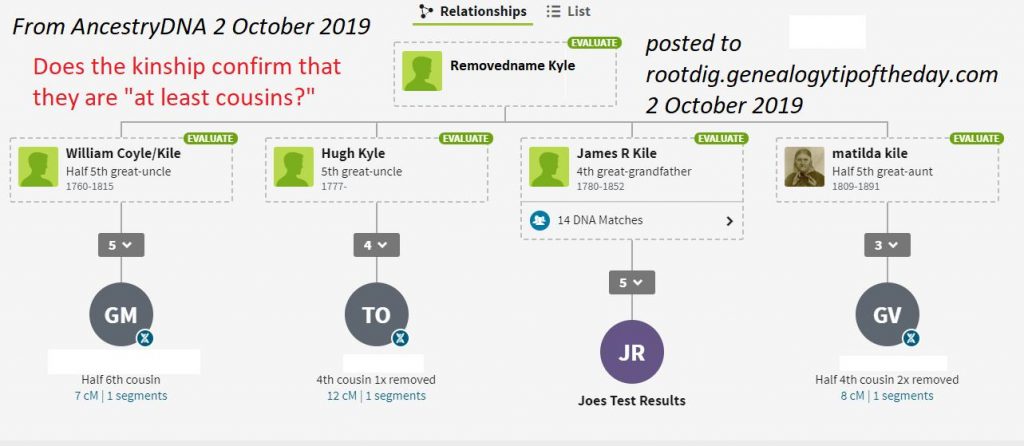

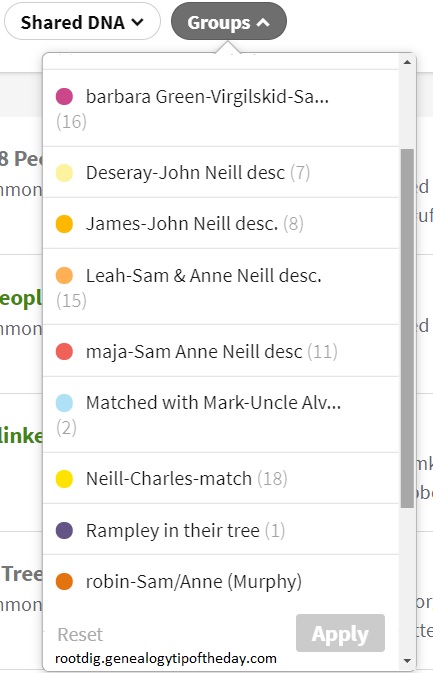

This post is a followup post to “A Shared DNA & Thrulines Question” that was posted […]

I use the online trees for the occasional clue when I am stuck as occasionally a […]

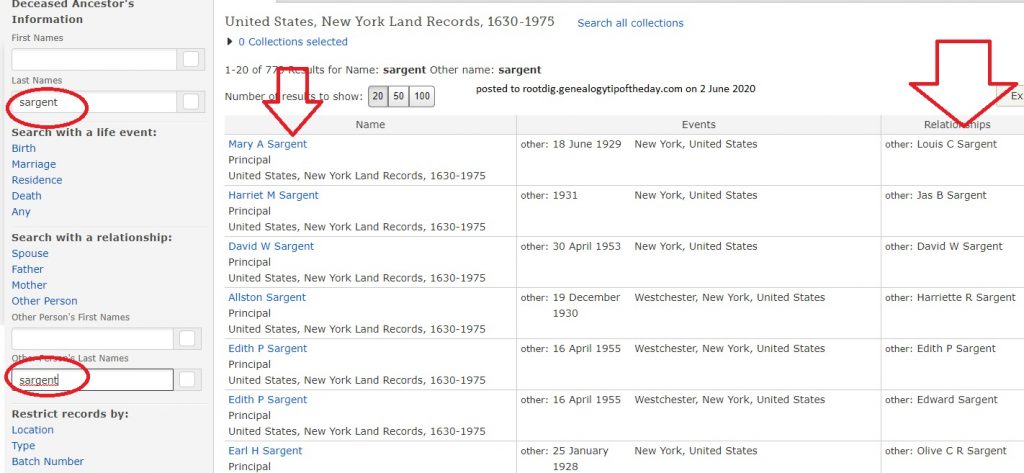

FamilySearch recently released “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975” on their website. While I appreciate […]

We are offering this 3 session class as an online download and a “go at your […]

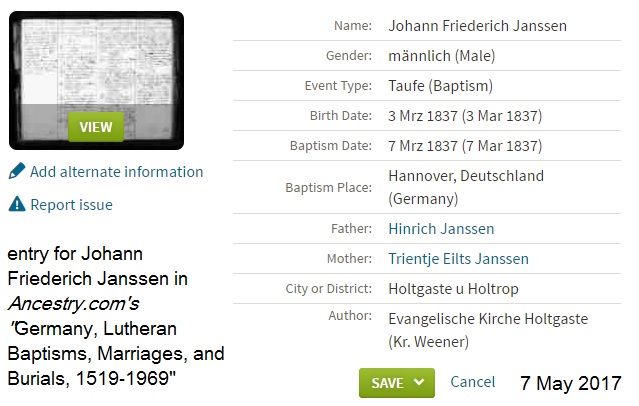

When I saw the index entry in Ancestry.com‘s “Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1519-1969” for Johann […]

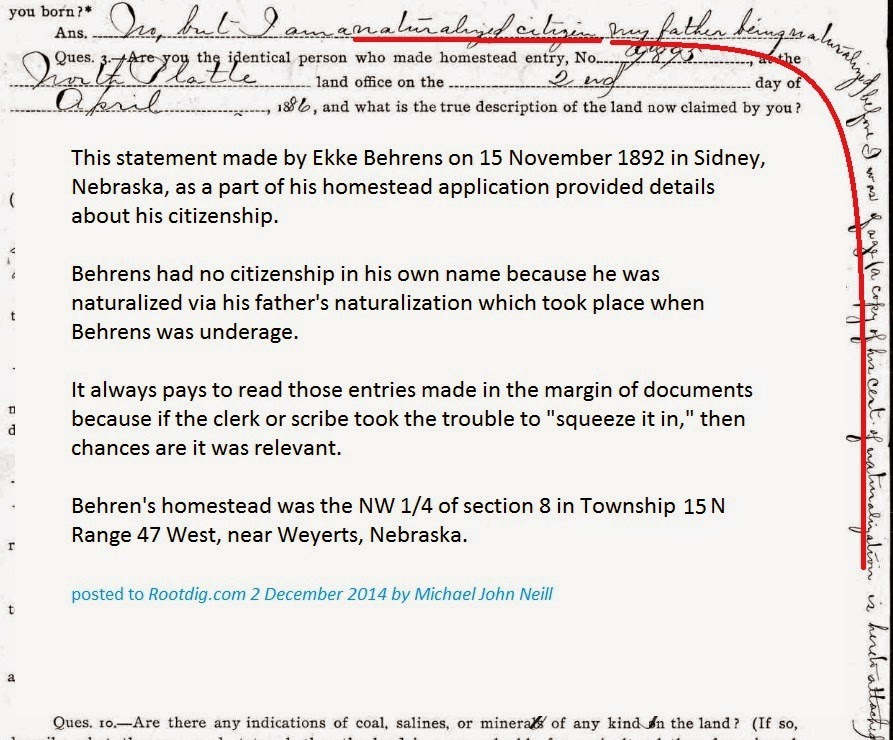

The 1892 homestead application of Ekke Behrens of Weyerts, Nebraska, makes several good genealogical research points […]

I am fortunate enough to have a significant collection of pictures from my parents, grandparents, one […]

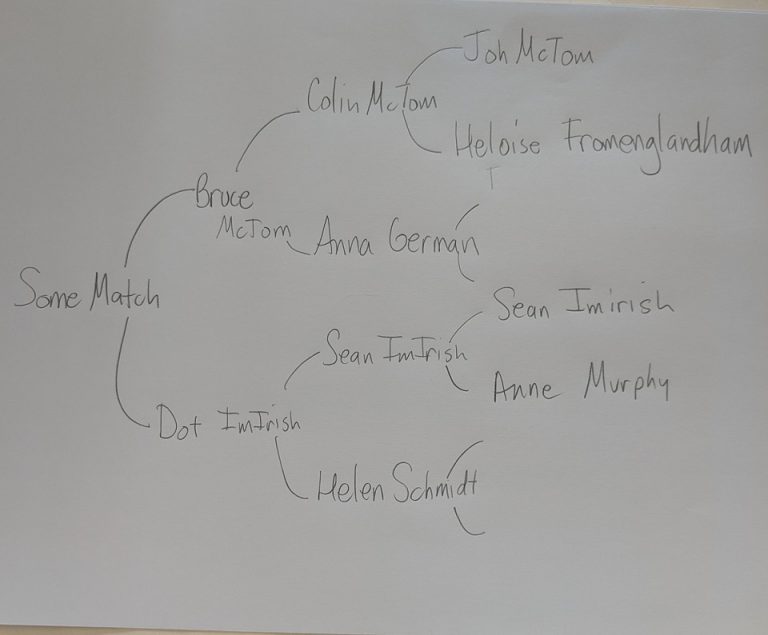

The details have been stripped since some individuals involved are still living. Working on a twentieth […]

Research is not just trolling for images of records and information. That’s gathering or harvesting. Research […]

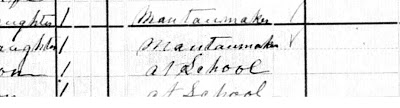

The question is the occupation of two daughters of Christian Troutfetter in the 1880 census for […]

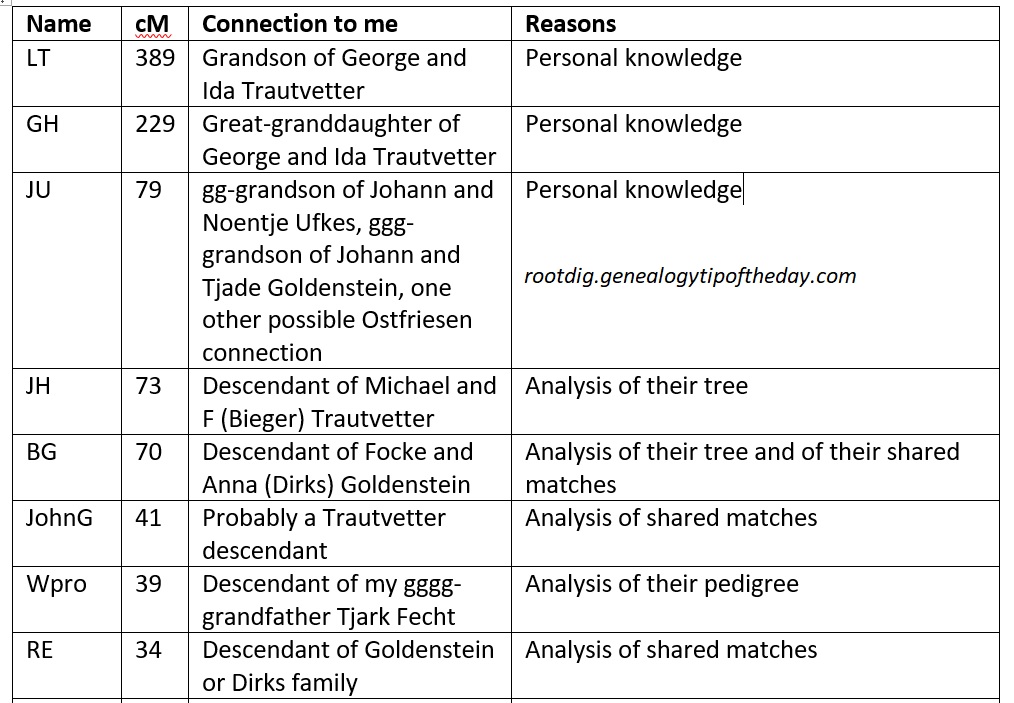

This post is not about how to complete a family tree to determine how you and […]

One reason I took a DNA test was so that I could make some discoveries on […]

My post on “Writing A Proof: Another Take” contained the phrase “Conduct a complete search of all relevant records that […]

Personally I think too many people “stress” about writing a proof argument. And I think that […]

Tamara Jones’ article on “Dutch Naming Myths” is a good, short, to-the-point read. Those whose ancestry […]

There are several reasons why errors appear in records. Have you ever thought while filling out […]

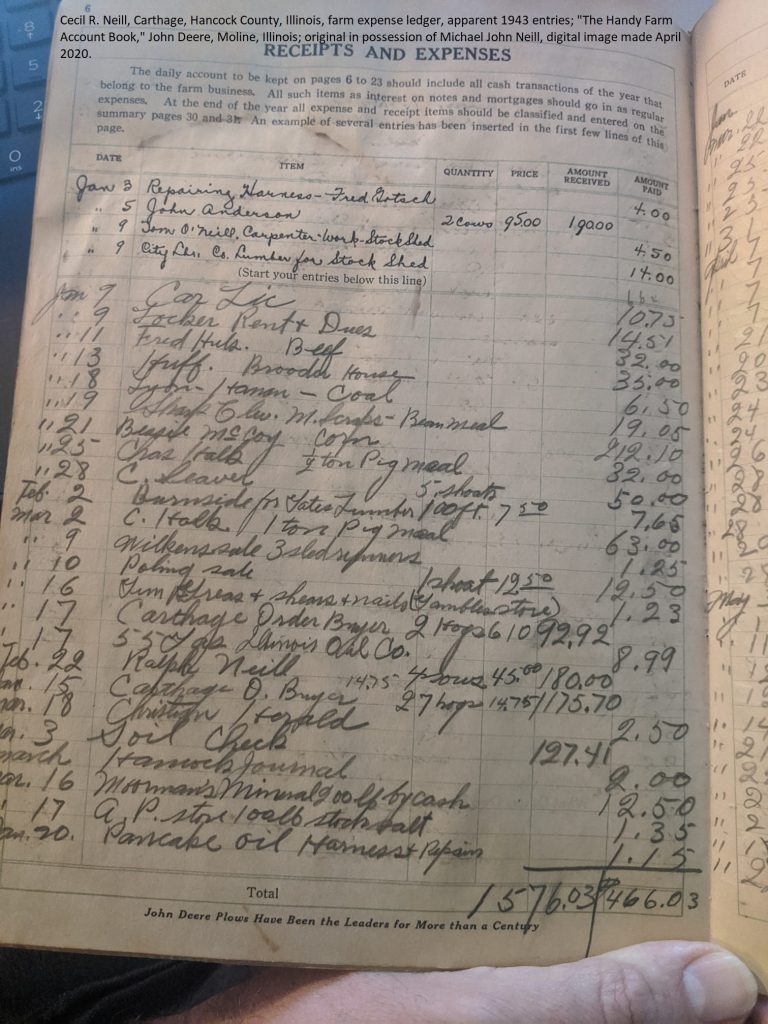

The ledger of my Grandfather Neill’s farm expenses only covers a few years in the early […]

It can be easy to get stuck in a rut even when one is solving problems, […]

Regular readers know that my family tree is full of relatives who are related to me […]

Years ago, early in my research I was having difficulty interpreting a phrase in an old […]

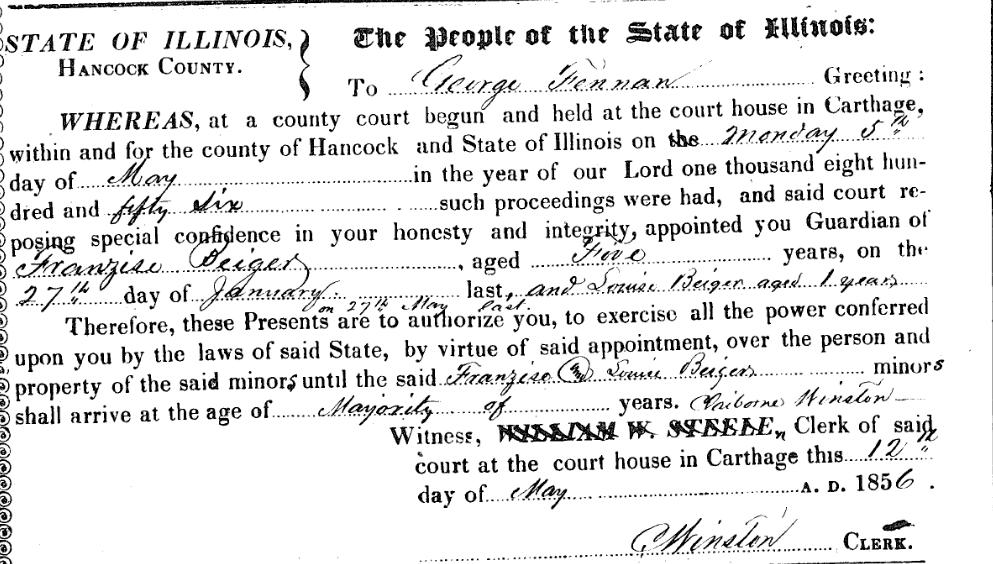

One is not always this fortunate. This record is from the guardianship of Francis and Louise […]

It can be a good problem-solving approach: asking yourself “where did they get that?” The “that” […]

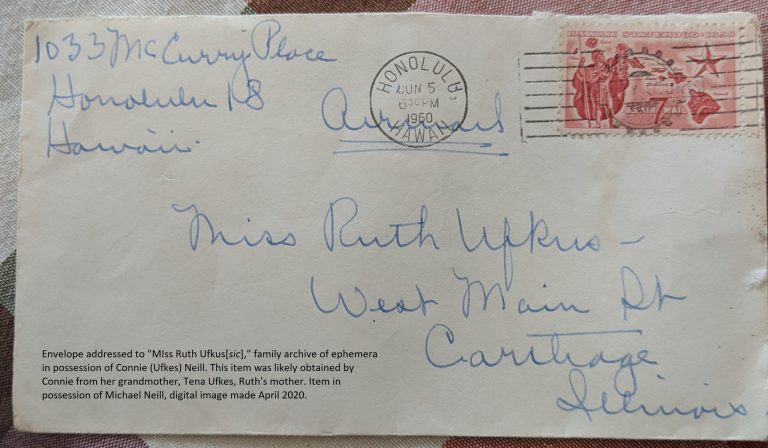

I will probably never know what the letter inside the 1960-era envelope was about or who […]

It’s always great to determine a DNA match–particularly when it is on a family you’ve been […]

Recent Comments