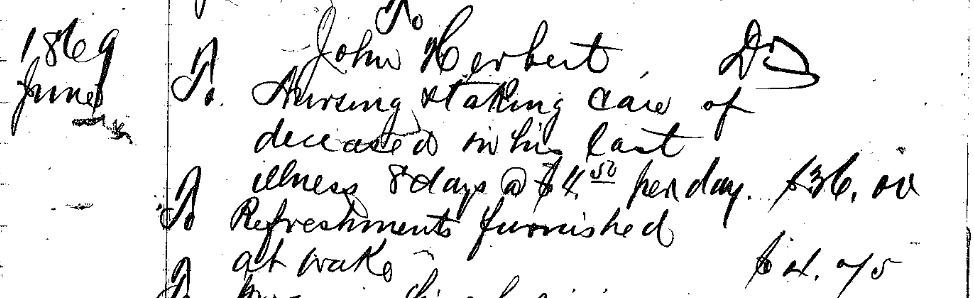

This image comes from part of an expense submission by John Herbert to the estate of […]

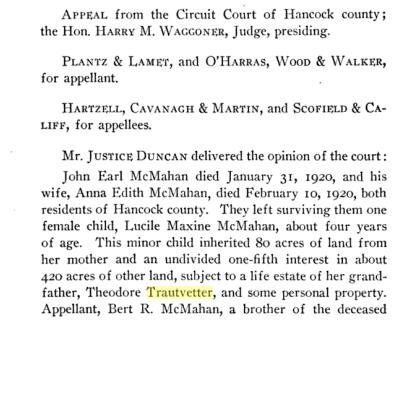

I discovered a court case that was appealed to the Illinois State Supreme Court while searching […]

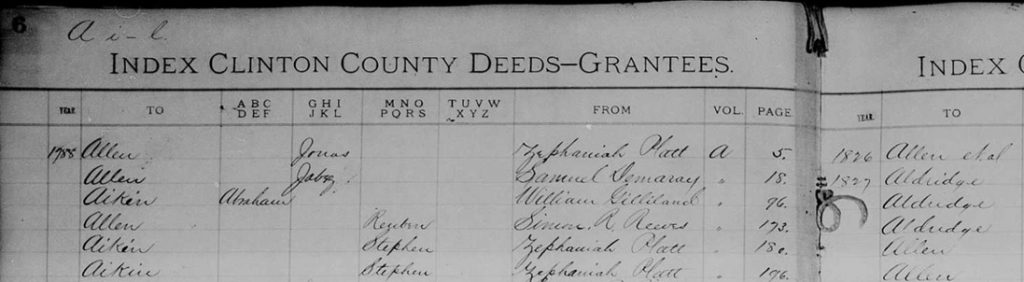

We are offering a new section of our “US Land Records” class during April and May […]

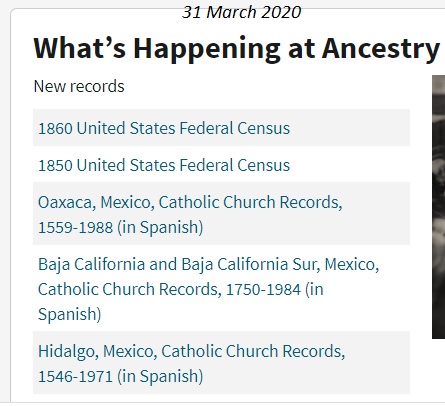

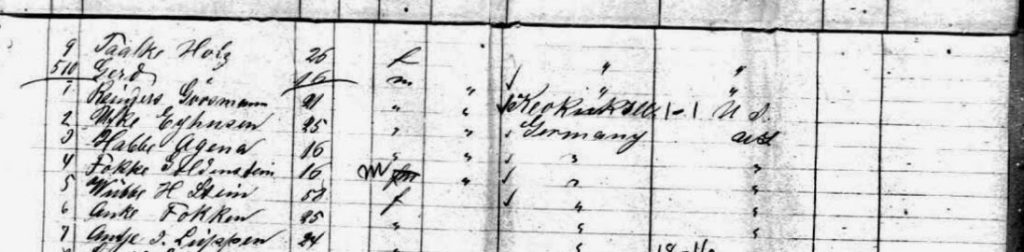

Not much to say other than what’s new about the 1850 and 1860 census at Ancestry.com? […]

rant alert: If this post about FindAGrave offends you, please unfollow, unlike, as appropriate. Do not […]

I’m even precisely certain when the picture of my grandmother Ida Neill and my oldest daughter […]

I read a blog post about citing research process and sources supposedly geared towards a beginner […]

In the old days of genealogy, we were told to fill out “research logs” where we […]

It can be easy to lament the lack of family history items such as photographs, bibles, […]

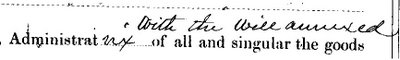

Typically administrators are appointed because there was no valid will left by the deceased. Yet there […]

Discovering Katharine Wickiser’s maiden name was Blain was a great find for me. Once you’ve been […]

In informal conversations with other genealogists and with my experiences in helping other researchers, there are […]

I’ve never been a huge fan of migration trails. Of course, how our ancestors got from […]

My father passed away on 7 March 2020 near his home in rural Carthage, Illinois. This […]

<attempted humor alert> I have a relative who was a Grass widow. Yes, a Grass widow […]

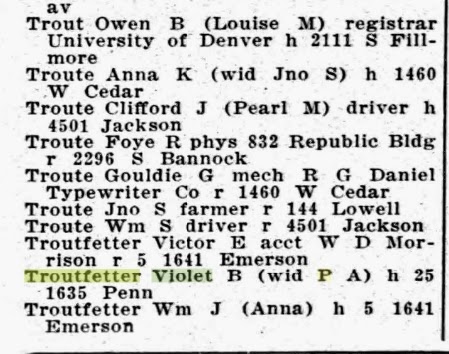

P. A. Troutfetter was dead by 1927. That is true. Whether that technically makes Violet B. […]

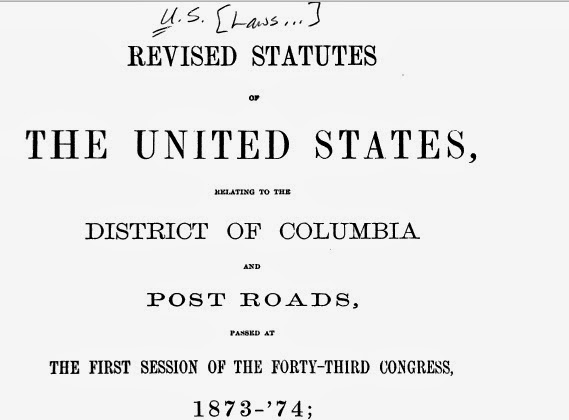

Googlebooks contains a scan of an 1873 Congressional Act “Revising and embodying all the Laws authorizing Post-Roads, in force […]

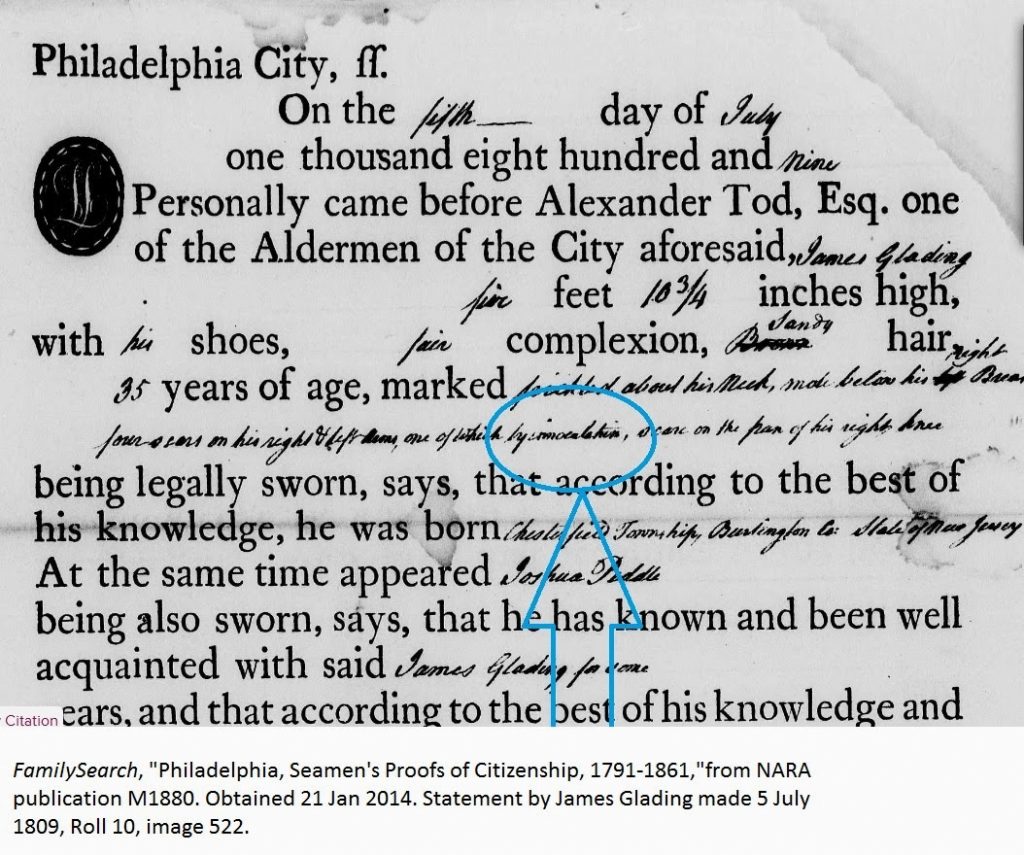

A scar “by inoculation” on this 1809 Seaman’s Proof of Citizenship likely refers to an inoculation […]

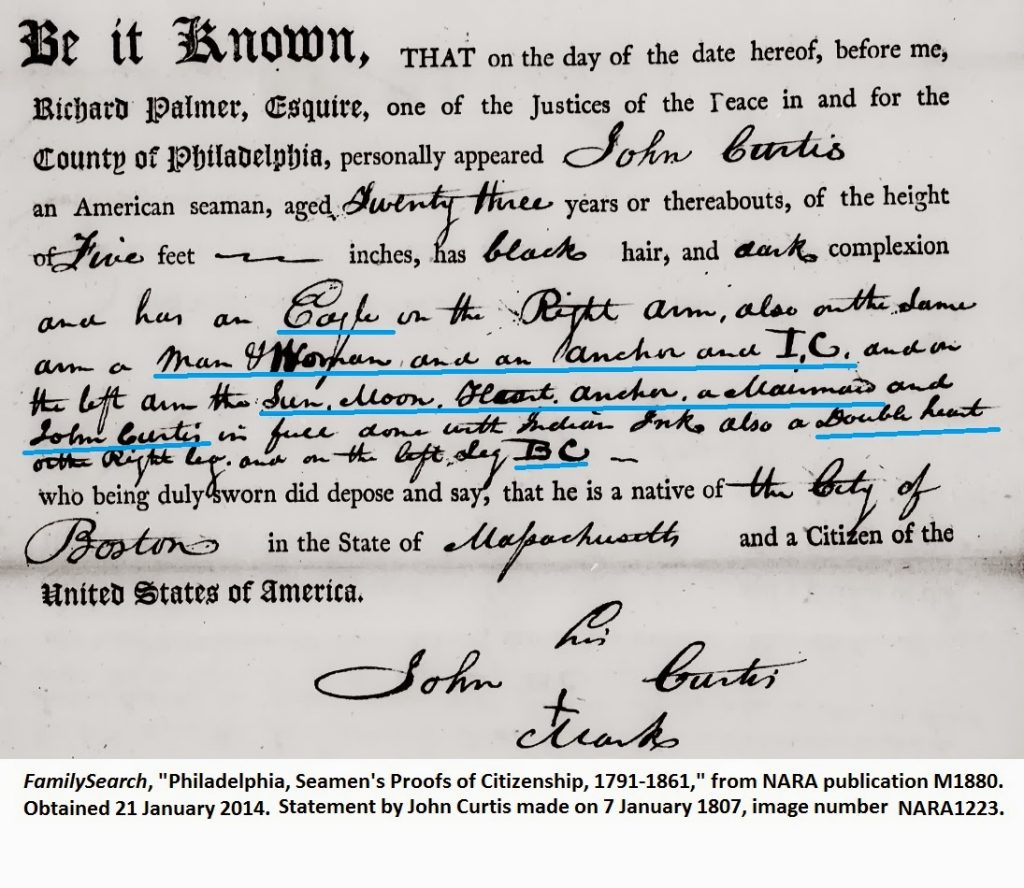

This 1807 seaman’s proof of citizenship from Philadelphia provides an interesting physical description: a number of tattoos. […]

On 1 January 1900, I had the following ancestors alive: Great-grandparents: Charles Neill Fannie Rampley George […]

Immigrants occasionally return to their homeland for a visit. Unfortunately for my research, ancestral visits home […]

I gave an interview on a local radio station about genealogy and the Genealogy Tip of […]

There’s a school of thought that some genealogists take themselves entirely too seriously and are so […]

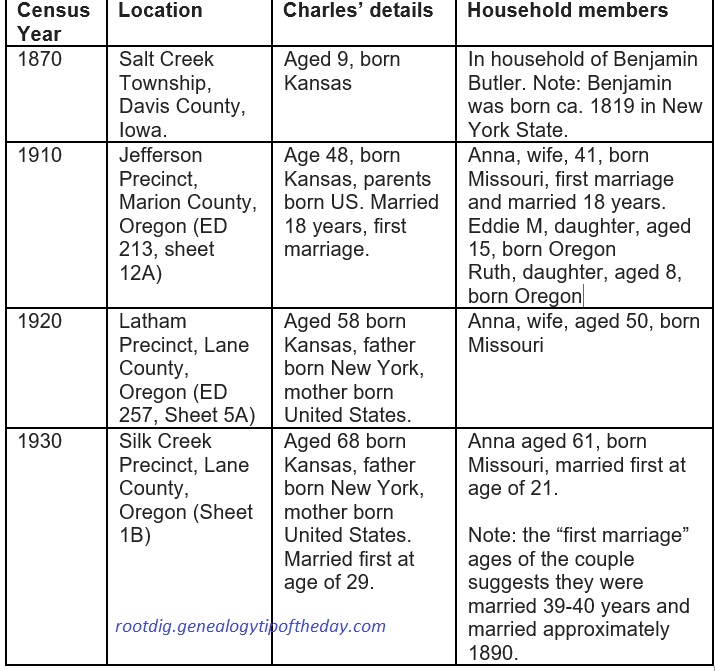

The chart summarizes information on a Charles Butler–that I think potentially are the same person. There […]

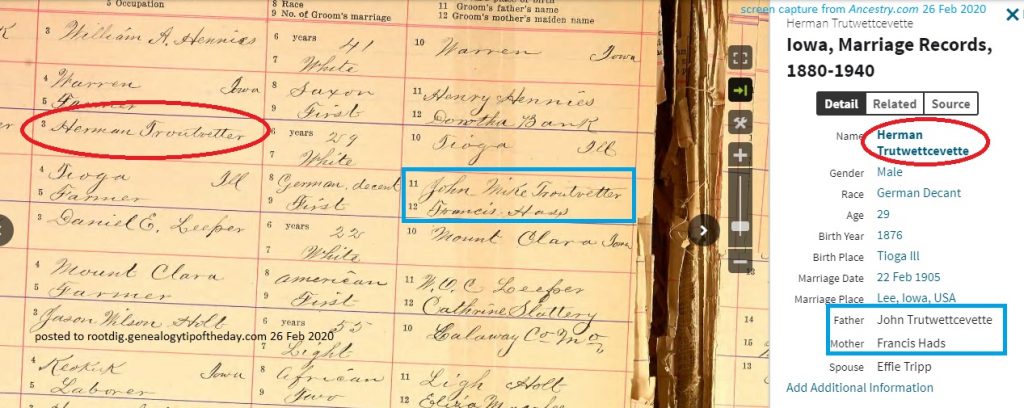

A researcher is never finished encountering incorrect transcriptions for a last name. But this one exceeded […]

I struggle with terms and definitions. In this blog post, I muse on “statements.” This is […]

Recent Comments