Get ready for research in 2021 with our “Brick Walls from A to Z” webinar on […]

A few months ago, I actually sat down and made time to actually read one of […]

I’ve tried to be very careful in my blog posts on the family of Benjamin Butler to […]

Give yourself or that genealogist on your holiday list the gift of Genealogy Tip of the […]

I’ve stripped the identifying details because these individuals were alive during my lifetime. The thought process […]

Irish research isn’t easy, but knowing what is available and having a plan can help. That’s […]

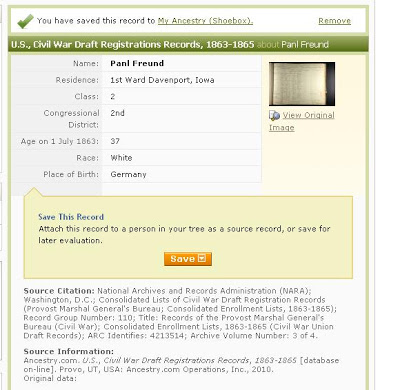

The screen above is one of the results from a search for “Freund” as a last […]

Sounds matter more than spelling. Consider a name as potentially being a match to your person […]

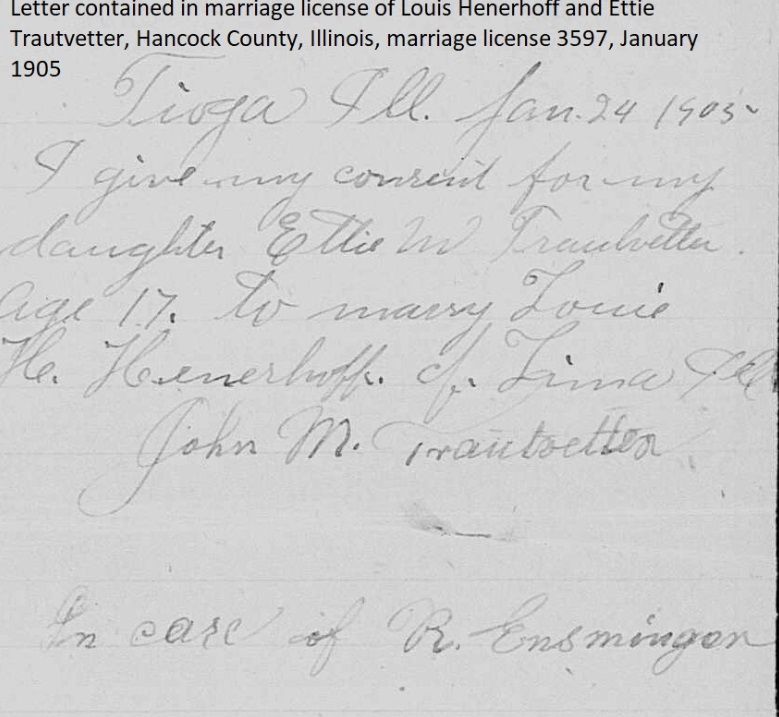

It took me years to locate a signature of John Michael Trautvetter who died in Hancock […]

I’m reading “They Were Her Property” by Stephanie Jones-Rogers. The 2019 release by Yale University Press […]

Determining if your ancestor filed a Timber Claim under the Timber Culture Act of 1873 can […]

Due to a scheduling conflict, we’ve moved our Beginning Irish research webinar to 30 October at […]

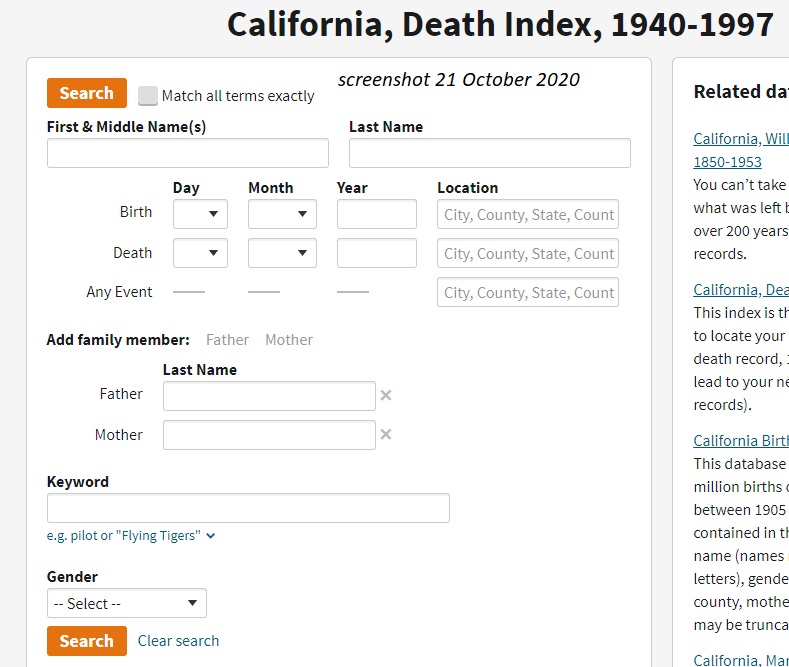

Ancestry’s “California, Death Index, 1940-1997” is one of those databases that contains data elements that are […]

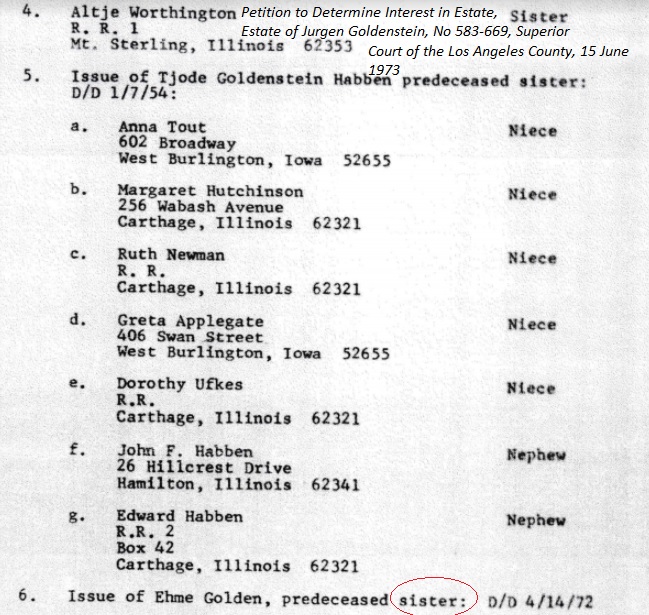

Jurgen Goldenstein died in Hawthorne, California, in 1972. His estate was probated in Los Angeles County […]

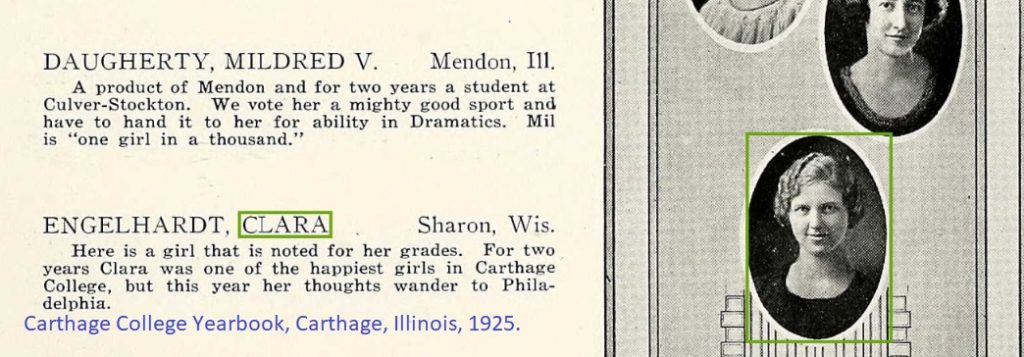

The 1925 Carthage College yearbook’s reference to Clara Engelhardt indicated that “this year her thoughts wander […]

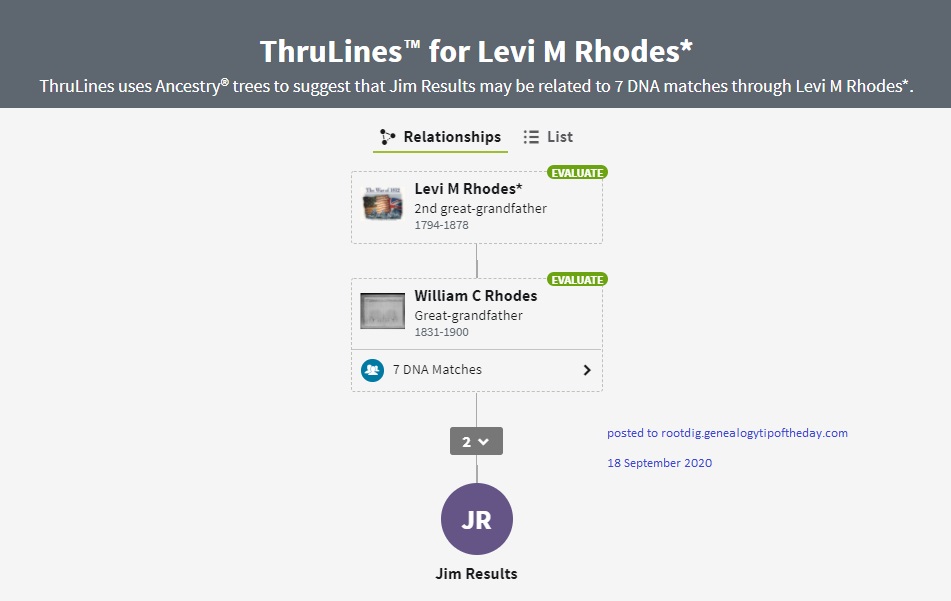

There was some time when I believed that William C. Rhodes (born in 1831 and lived […]

We are excited to offer new and updated sessions of these two popular presentations. If you […]

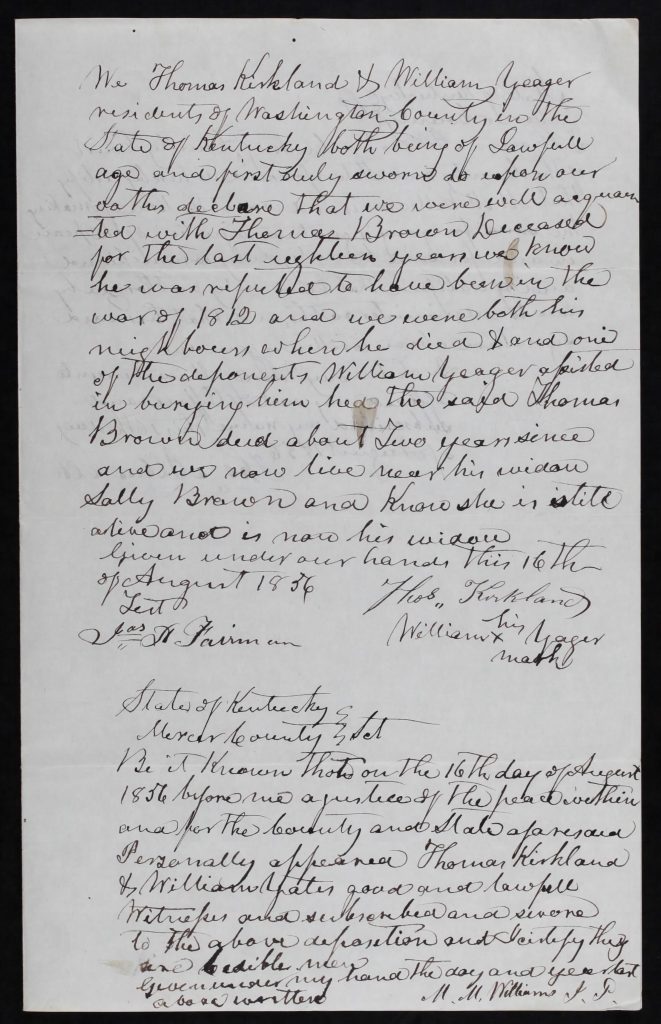

Widow’s pension applications are full of statements by neighbors, associates, and relatives testifying to the marriage […]

Readers know that I hate genealogy “games.” I think most of them are time wasters and […]

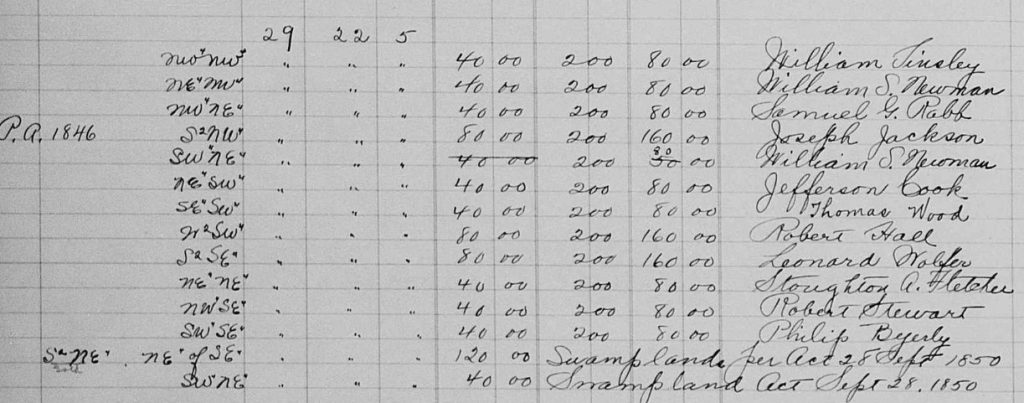

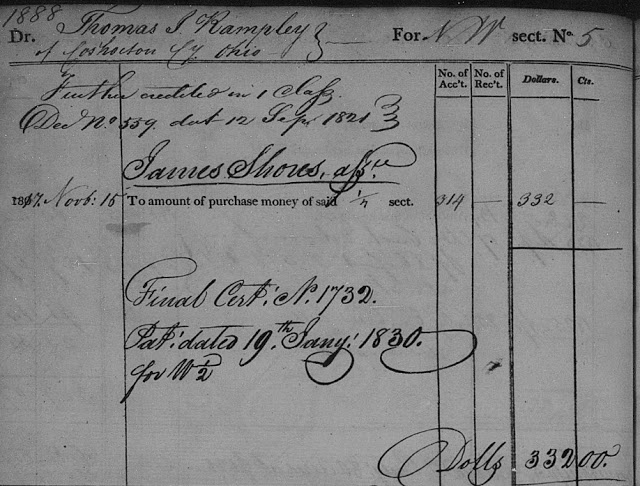

FamilySearch has had the Bureau of Land Management Tract Books (titled: United States, Bureau of Land […]

There is something gratifying about finding your ancestor’s name in a record, particularly one that is […]

Even seemingly meaningless clippings like this reference to a broken hip can be useful. This item […]

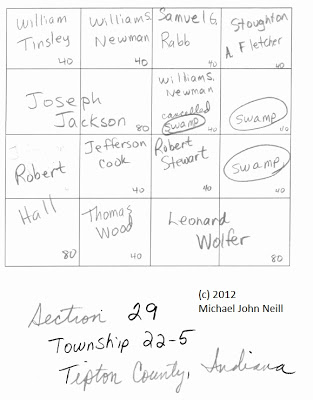

It is not fancy, but it is functional. I find it easier to make initial drawings […]

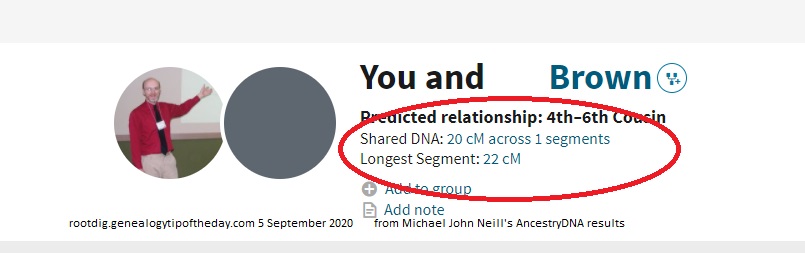

At first it appears confusing. One of my AncestryDNA matches shows us as sharing 20 cM […]

The ability to merge sources (particularly census) into a tree at Ancestry.com is really a nice […]

Recent Comments