I’ve taken an ancestral incident in Kentucky in the early 19th century and turned it into […]

We’ve still got room in our prepping for the 1950 census release webinar. Ordered recordings will […]

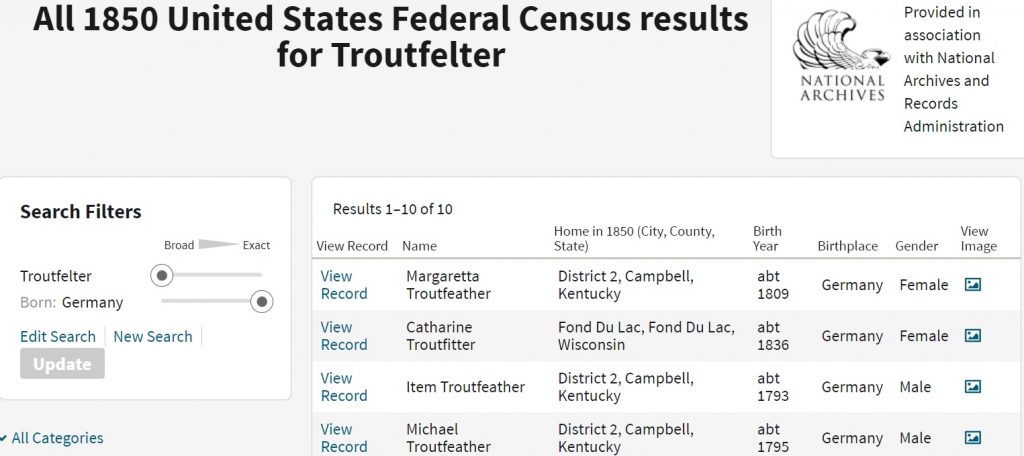

Broad searches are fine as long as they work in a way that the researcher expects. […]

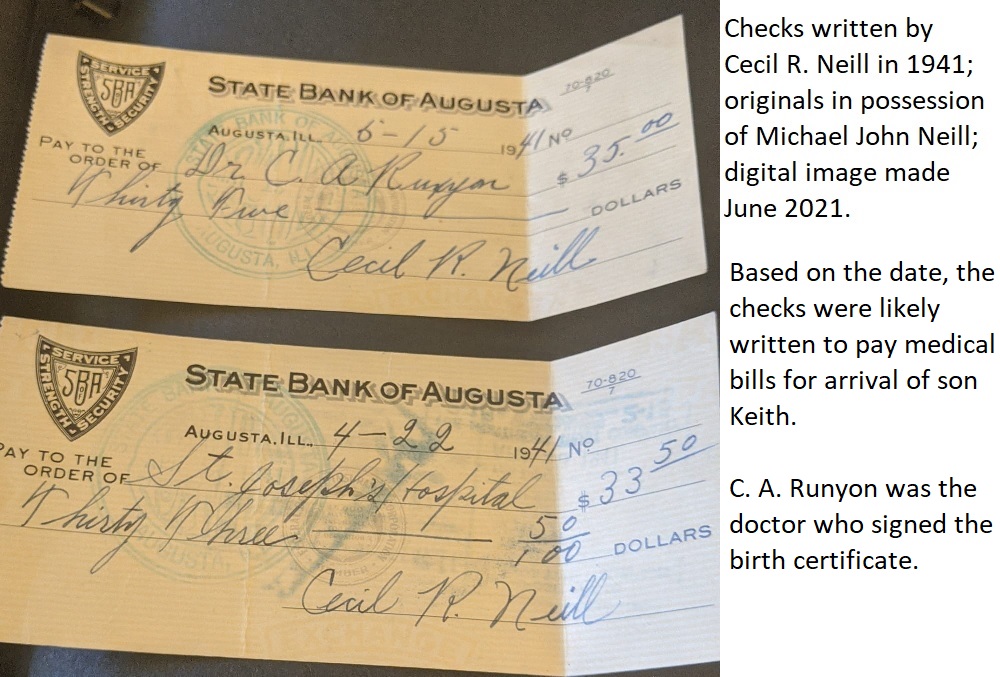

I wrote about these checks from my Grandpa Neill in Genealogy Tip of the Day but […]

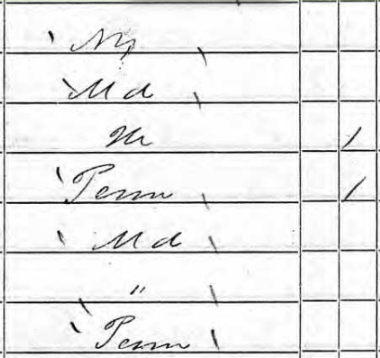

I’ve been using a death register from Adams County, Illinois, in the 1870 and 1880 time […]

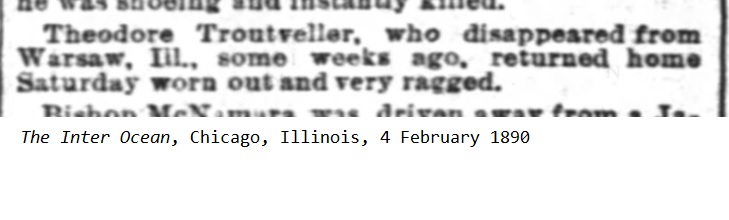

I’ve known about Theodore Trautvetter’s disappearance from Warsaw, Illinois, in the early 1890s. I also know […]

We are offering another session of our 5 part series on US land records that runs […]

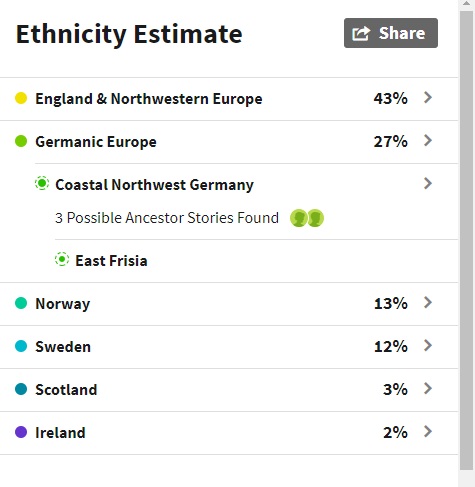

One of the reasons for having my father-in-law do a DNA test at AncestryDNA was to […]

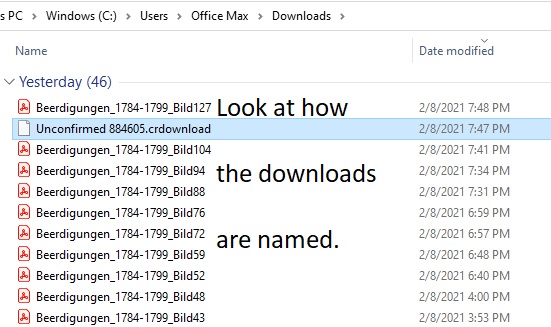

Downloading images from websites for personal research use is always advised. Then the researcher has the […]

The picture based on my Mom’s memories got me thinking about genealogical research and how we […]

The red rocker in the picture is nearly eighty years of age and is in amazingly […]

AncestryDNA‘s ethnicity estimates now include East Frisia–more affectionately known as Ostfriesland. I’m glad to see they’ve […]

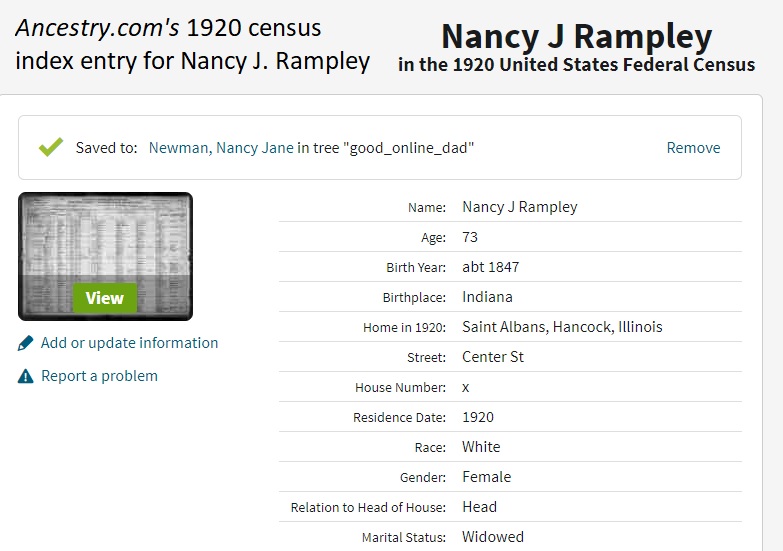

Ancestry.com’s 1920 census index transcription for Nancy J. Rampley of St. Albans’ Township, Hancock County, Illinois, […]

One of my DNA matches, Katherine, is a descendant of my ancestor, Samuel Sargent. Her tree […]

It’s probably not correct. The probability that in the 1880s a man travels across the state […]

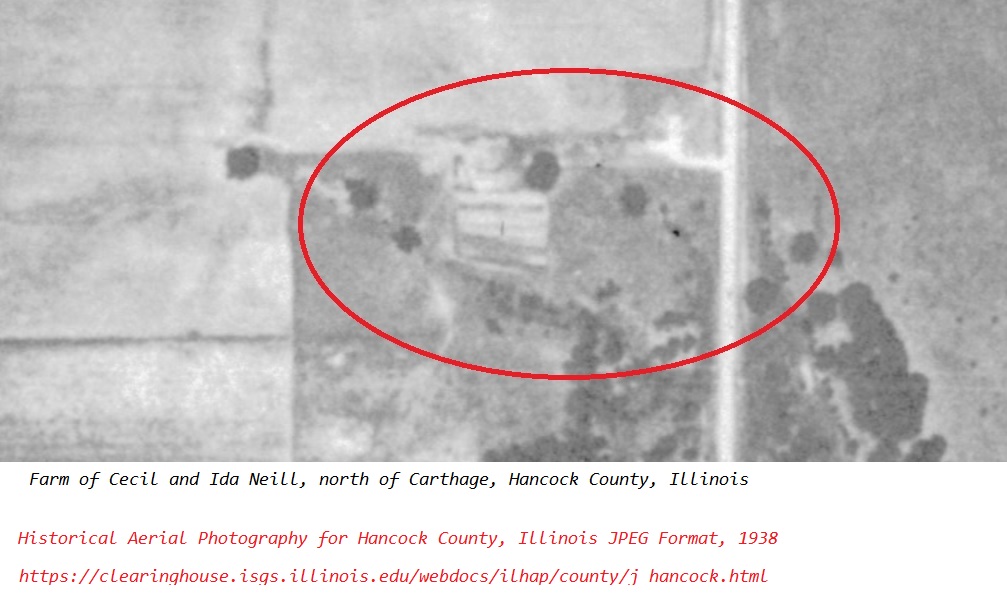

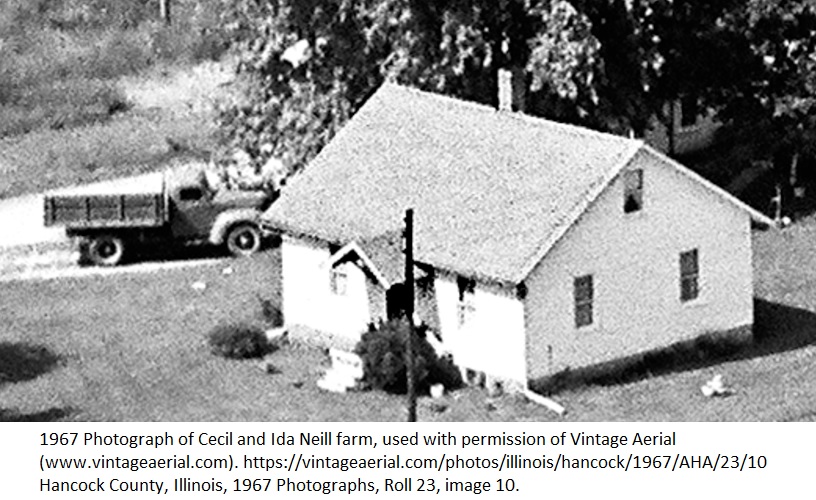

It took some doing to find this 1938 aerial photograph of my grandparents’ farm in Hancock […]

I will be offering this five-session class starting 4 January 2021. More details on our announcement […]

It’s often referred to as “correlation and analysis” in genealogical methods courses, but a certain aspect […]

Genealogists often lament errors in census records. I’m not certain census records contain any more errors […]

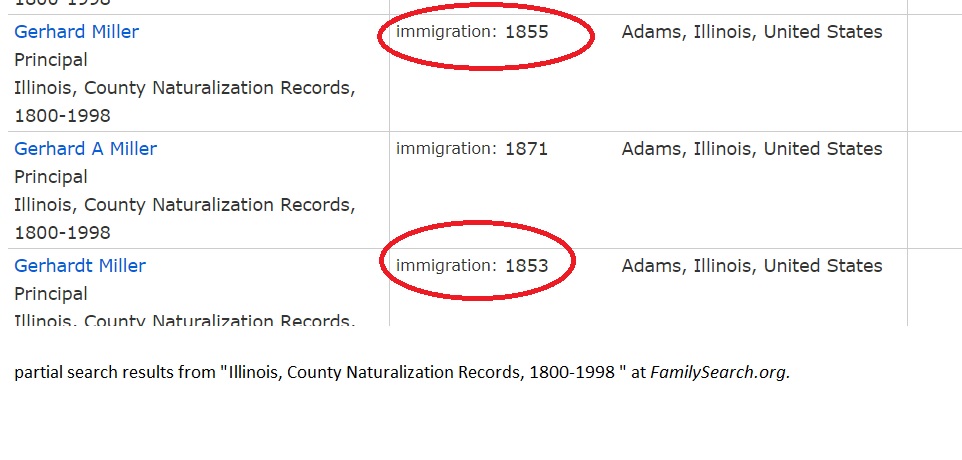

The search results for Ger* Miller in FamilySearch.org‘s “Illinois, County Naturalization Records, 1800-1998” lists several entries. […]

I usually hate the phrase “Yes, but…” because the “but” is often followed by an excuse. […]

There’s a school of genealogical thought that essentially says “writing about the genealogy research process is […]

I can almost see a barefoot Grandma Neill in the backyard of this picture, headed towards […]

We’ve released the recorded version of our 2020 “Genealogy Brick Walls from A to Z” webinar. […]

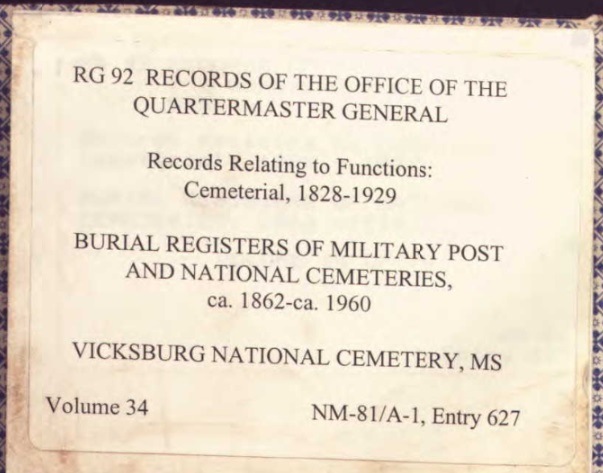

The list of burials in the Vicksburg National Cemetery in Vicksburg, Mississippi, testifies to the number […]

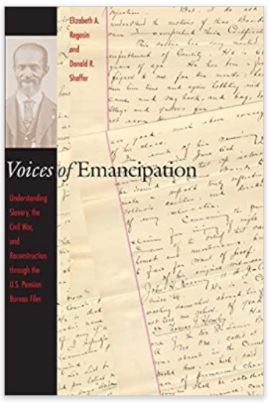

I was leafing through Voices of Emancipation and got to wondering if any of my forebears […]

Recent Comments